When I visited Divya Mehra’s exhibition The End of You at Night Gallery in Los Angeles recently, an audience favorite was “We’re Ready to Believe You!,” a 30-foot-tall inflatable Stay Puft Marshmallow Man lying flat on his diabolical white face. I’ve been following Mehra’s work since we first met in 2017 (full disclosure: the artist and I are friends and I wrote the press release for The End of You). Divya and I have had many conversations about her art and its acerbic commentary on colonialism and racism, subjects that affect us both. Her large-scale works, like the marshmallow man or the 2023 golden genie lamp sculpture “Your Wish Is Your Command,” entice audiences with their incisive humor and impressive scale before confronting them with violent histories of the subjugation and exploitation of people of color.

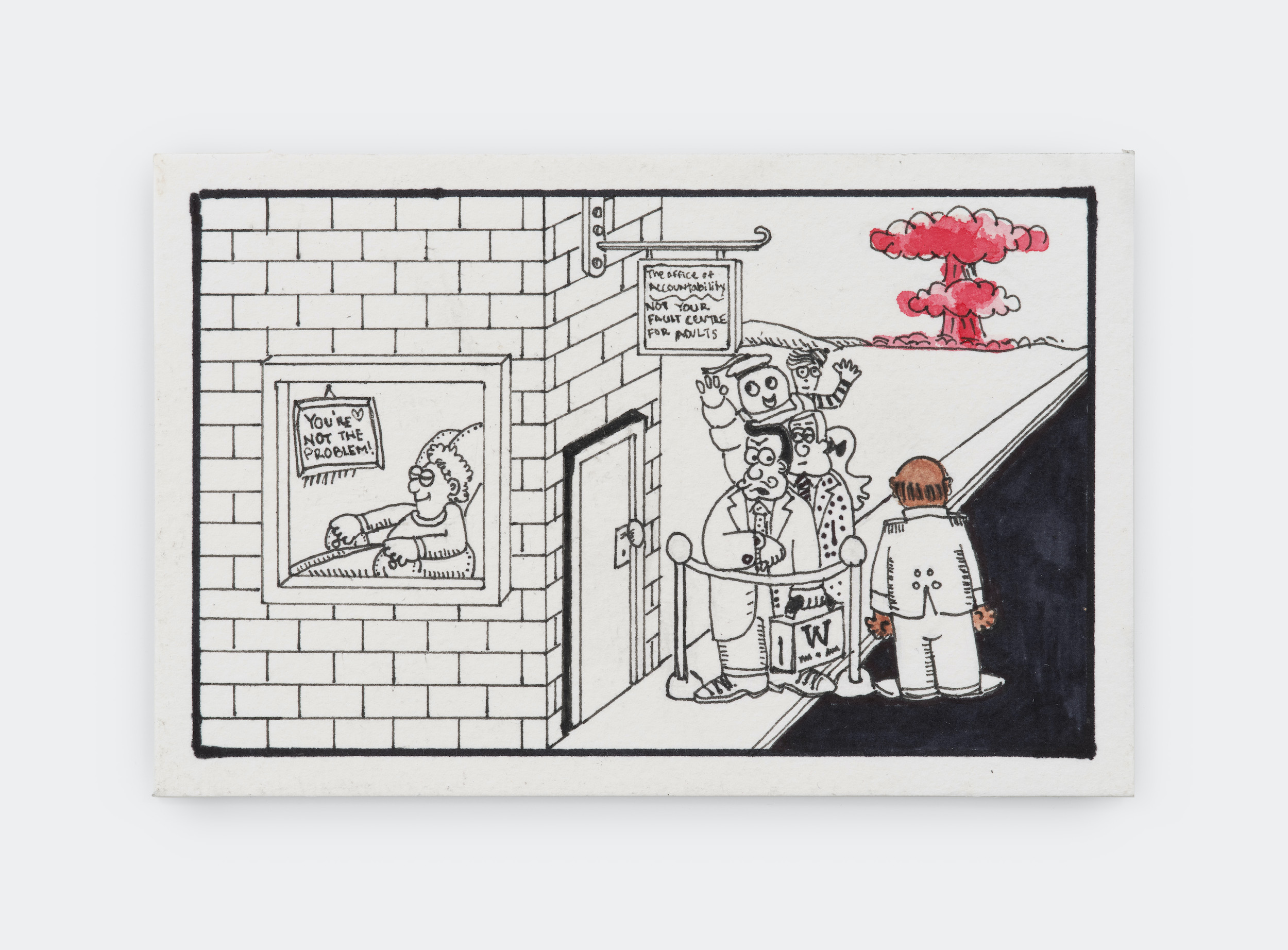

But the works that resonate most with me right now are a series of small marker and watercolor drawings also titled The End of You. Radically reimagining cartoonist Skip Morrow’s 1983 book The End, most of the five drawings portray a person of color observing an explosion in the distance while White people go about their business, oblivious.

When Mehra printed the drawings as postcards for the Wattis Institute in San Francisco in 2020, the end of the world seemed nigh for many, but the cherry red explosions they depicted felt more metaphorical than literal. Now they’re metaphors for the destructive repercussions of colonialism and systemic racism that are all too real for people in Gaza and beyond.

A few months ago my mom and I saw the Egyptian comedian Bassem Youssef in concert in Detroit, among a primarily Arab-American crowd (myself included). Youssef joked, more openly than usual I assume, about the Biden administration’s fealty to Israel and the crowd cheered in agreement. As a Michigan native, I’m sure that the democrats sealed their loss in the state months ago, but now we have a larger problem: a xenophobic racist president-elect who will almost certainly enable Israel’s continued attacks on Palestine, and a rapidly spreading war.

More than ever, I identify with the person in Mehra’s drawings: watching the explosion, helpless, as it threatens to decimate what could be Baalbek, in Lebanon, from where part of my family hails. Then I look at the drawings’ other figures, lined up at the “not-your-fault” center. For some of us, oblivion is always out of reach.