In the morning, glinting tessellations of light sheathe the massive interlocking shapes of the cobalt blue glass of the Lippo Centre in Hong Kong, which appears to expand and contract. On the other side of the world, the sun’s rays rake across the striated concrete facade of the Art and Architecture Building at Yale University, each facet of its Roman bulk sequentially shading another.

For Paul Rudolph, the architect of both of these buildings, a key design goal was a return to monumentality, a deliberate shift away from the ethereal soaring steel and glass structures that dominated mid-century America. Twenty-seven years after Rudolph’s death, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is presenting the first museum show dedicated to his life and work, largely organized around his renowned presentation drawings, with supporting ephemera. His legacy is decidedly mixed; his works are endlessly litigated, both in the realm of public reception and also frequently in courts, with many under threat of demolition or redevelopment. But the conspicuously monumental concrete buildings for which he is primarily known today are a fraction of the output of this vanguard architect, who was regarded by Walter Gropius as the star student among future luminaries Philip Johnson and I.M. Pei.

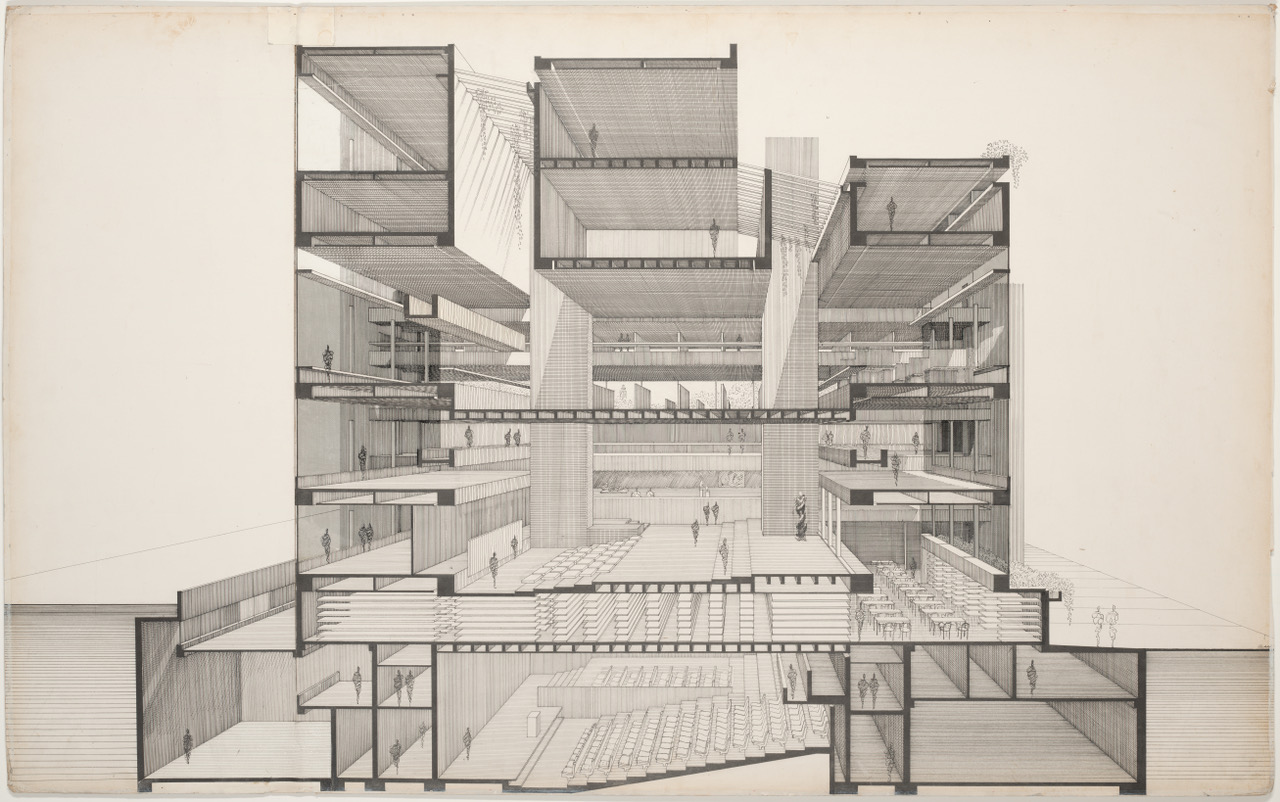

Rudolph’s notably prodigious output of drawings rewards close looking: Spaces are articulated through sharp cross-hatching, shifting densities of lines yield volume. When color is employed, it is used sparingly, often accenting construction requirements or revisions. While his draftsmanship has long been celebrated, it is the clarity of his proposals that maintain their relevancy.

In 1967, Rudolph accepted a commission from the Ford Foundation to create an alternative proposal for urban planner Robert Moses’s Lower Manhattan Expressway, often breezily referred to as “LOMEX.” The resulting plan, represented in four large drawings, was a vision in line with the development-minded ethos of the era that would have created thousands of units of housing at the cost of radically altering the fabric of the neighborhoods in its projected path. Instead of Moses’s city-bisecting elevated 10-lane highway, Rudolph’s scheme opted for a less disruptive below-grade roadway, a “two-mile building” that linked the Holland Tunnel with the Williamsburg and Manhattan bridges with A-framed blocks of modular housing built atop. Rendered in “Perspective drawing of the Lower Manhattan Expressway / City Corridor project (unbuilt), New York” (1967–72), the hub is a fantasia of urbanity, with extravagantly cantilevered monorail tracks arcing out over the inescapable, if tastefully hidden, highway and surrounding interchanges.

50 years later, the LOMEX proposal seems the very height of mid-century hubris. Rudolph certainly built for the moment, but like all architects, he also hoped to build for history. In his drawings, people are rendered most often as futurist swirls of dynamic coiled lines. The city itself is often reduced to a wireframe scrim, dialing down the din of urbanity for the masterplan so carefully drafted. Of course, the surrounding environment would have amounted to more than static texture for its residents.

The world that Paul Rudolph foresaw is best viewed in glimpses — his “Rolling Dining Chair” (1968) simplifies as it complicates, reducing seating to planes of lucite secured to a tubular chrome frame, a design that knitted together light and space to create an effortless sense of airy contemporaneity. When rendered as physical models, Rudolph’s works could stretch architectural understanding, at times too far for practical consideration. Perhaps this was an inherent fault in his practice: His designs are best appreciated through the infinite plane of the drafting table. Rudolph’s unbuilt projects live on as unborn dreams, specters of progress that, even when confined to vellum, widen our vision.

Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) continues through March 16, 2025. The exhibition was organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in collaboration with the Library of Congress’s Paul Marvin Rudolph Archive.