I can’t recall with certainty when I first read James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues,” but I had it well in mind in 1984 when Raymond Carver and I were selecting stories for our American Short Story Masterpieces. When Ray and I worked on our selections, we would meet in Manhattan, where I lived, or in Syracuse, New York, where he lived. Whichever of us had traveled brought a suitcase full of books, and the other contributed an accumulated stack. We’d trade books.

Article continues after advertisement

Each morning we’d read and then meet for lunch and talk about what we’d read. After lunch we’d read some more, and at dinner we talked about the afternoon’s reading. Sometimes we’d reread at the other’s behest. Our conversations were not analytical. Typically, the recognition of a story for inclusion was an immediate, mutual response: “Wow, that’s a great story! Yes!” Conversation ended there, in certainty, with a selection easily made.

Auden noted, “Pleasure is by no means an infallible critical guide, but it is the least fallible.” Anyone who reads professionally, as an editor, writer, teacher, agent, or publisher, becomes readily aware of the overwhelming mediocrity that attends most literary effort. Amid the mediocrity—the baseline static or white noise, cliché, approximation, and shorthand—that necessarily suffuses daily life in order that the effort of communication doesn’t exhaust everyone, the presence of originality, wit, authenticity, and truth announces itself like a seismographic spike to anyone receptive to the quality of accurate experience. Innately, within every reader, even a jaded, hypercritical professional reader, such as an editor or teacher burdened by mountains of manuscripts can sometimes tend to be, there is what I call an innocent reader.

Bringing readers into an experience of shared humanity, Baldwin resists posing his characters purely as victims.

Eudora Welty, in her memoir One Writer’s Beginnings, recalled that as a child when she was read to, and ever after when she read to herself, she always heard a voice. What was the voice that Welty heard? She implied a discernible, constantly reliable authenticity that resides in language and that transcends the personality of the writer, though the writer’s personality speaks in every line. The source of this authenticity is the rhythmic nature of language—the voice of literature. When one reads Jane Austen, Virginia Woolf, Tolstoy, or any other great writer, one literally hears and experiences the presence of the author and simultaneously experiences what occurs only when a work has transcended the purely personal and risen to the sphere of the universal. The recognition doesn’t require rationalization. You know it when you hear it, instantly, always. And so it was when Ray and I shared “Sonny’s Blues”—Wow! What a great story!

Reading is good; rereading is better. I can’t say with certainty how many times—forty? fifty?—I’ve read “Sonny’s Blues,” only that for more than thirty-five years I’ve been reading and teaching the story to writers who are developing their art. In classes I ask students to read their works aloud, and I read aloud the work of the writers we’re studying. Good writing has a rhythm that embodies the characters’ lives moment to moment and provides the narrator’s mediating presence. In editorial and classroom discussions of work, a comment sometimes comes that a beat has been missed—literally, it’s a heartbeat. The heartbeat is the syllable, the breath is the line. Not all heartbeats and breaths are the same, of course. The muscular activity of uttering sound springs from the emotional and intellectual experience of life. Words proceed from a unity of mind, body, idea, and emotion. Before words reach the page, the writer locates the core of each rhythmic phrase and lets it come to life so that it touches and quickens the reader’s heart. Without this connection between writer and reader, the other elements of writing fall flat.

When I ask students to read their work aloud and a piece isn’t working well, I sometimes stop listening to the words and listen instead to the thrum of the voice. Is it coming from the head only, or is it coming from the center of the body, from the heart and loins and stomach as well as the head? What are the moods, prevailing emotions, needs, or desires being expressed? Do they correlate naturally and spontaneously, with the words riding the rhythms, or are the words and rhythms forced, and if so, why, and how might the utterance be improved? How aware is the writer of what the writing imparts to the reader? Is the writer asking the reader to receive ennui, fear, anxiety, irritation, gloom, or confusion unalloyed by hope, affirmation, joy, sympathy, or love? How might the writer come into contact with the impulses driving the work and make more conscious, or at least more effective, choices about the play of language?

Baldwin doesn’t judge; he observes, leaving his readers to judge.

Coleridge’s definition of poetry—the best words in the best order—applies to prose as well, and if a story succeeds, the words carry the reader all the way home, back to life outside the story, having received gifts along the way. “Sonny’s Blues” is such a story, an eternal one, a masterpiece that requires no explanation, yet there’s pleasure in observing how and why Baldwin wrote a story that’s long been read in schools everywhere, illuminating human experience and influencing civilization for the better.

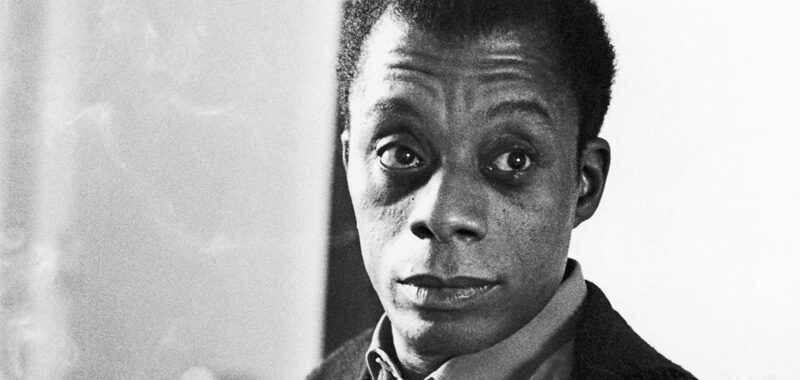

Baldwin was thirty-three in 1957, when he published “Sonny’s Blues,” and it might be said that thirty-three years, or the whole of his lifetime, went into the story. Readers today coming for the first time to this story of Harlem life and heroin addiction might view it in contemporary terms, and there’s no harm in that. The messages in the story are as old as the biblical allusions Baldwin employs in the contrast between darkness and light, and as evergreen as ordinary human emotions, yet it’s well to recall that in 1957 there was no Civil Rights Act, the struggle over Jim Crow laws and segregation had a long way to go, and racial conditions and inequalities were deplorable and disregarded by most white Americans.

The story, which poses two brothers’ estrangement over addiction and their ultimate rapprochement as a quietly implicit analogy to racial division and an inspiration toward unity and love, rides, as its title suggests, on music, specifically jazz. Baldwin was well aware that jazz was the first form of entertainment to be integrated. Bringing readers into an experience of shared humanity, Baldwin resists posing his characters purely as victims and allows for the view of anyone who may not agree with being included in a particular group of others—for instance, a white reader, on the one hand, and Black American experience, on the other.

Baldwin doesn’t judge; he observes, leaving his readers to judge while being drawn toward fairmindedness amid lyric writing that culminates in a transcendent jazz performance by the title character playing piano with a combo in a Village nightclub, where only a reader with a heart of stone will fail to have been moved to tears of recognition, sorrow and joy, in a triumph of love over fear. But the triumph is never final and must be fought and won again and again, day by day, moment to moment, and that dire necessity, which anyone might well wish to deny, calls on everyone to engage on behalf of love.

__________________________________

James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” by Tom Jenks will be published by Oxford University Press in October 2024.