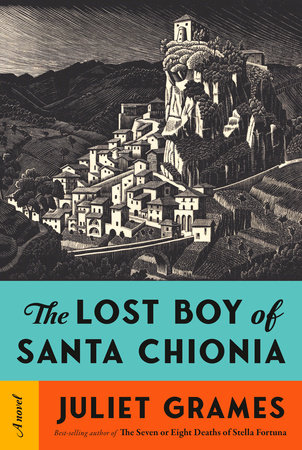

The following is from Juliet Grames’ The Lost Boy of Santa Chionia. Grames is the best-selling author of The Seven or Eight Deaths of Stella Fortuna. Her essays and short fiction have appeared in Real Simple, Parade, and The Boston Globe, and she is the recipient of an Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. She is editorial director at Soho Press in New York.

How had I, an American college girl, arrived at a mountain precipice in the remotest hinterlands of Italy, in this village “forgotten by God and by man”? Well, on foot, for there was no other way to get there (technically I had declined the offer of a donkey).

Article continues below

On Tuesday, August 30, 1960, I had first made the three-hour mountain-cresting journey from the village of Bova, where the nearest drivable road ended. I was escorted by Dr. Teodoro Iiriti, the kind, bluff-faced cardiologist who had first petitioned my employer, the charity fund Child Rescue, to assign an agent to his indigent hometown; accompanying us were two nuns from the Bova convent. Chaperones. It was 1960 across the rest of the world, or at least some parts of it. But in the Aspromonte it was the Aspromonte.

I was not prepared for Santa Chionia—but what could have prepared me? Nothing anyone had told me turned out to be untrue, not even the things that contradicted each other. Santa Chionia tolerated no discomfort with paradox.

She emerged from the valley as her virgin martyr namesake must have emerged from a bath, springing up abrupt and dripping behind the mountain dewlaps that shielded her from the lascivious view of the sea. The rising sun glinted off her façades. The suddenness—where there had been only the thick silence of the mountains, now there was an ancient civilization.

The paese was an island cut from the mountainside, its medieval stone houses tessellated directly into the cliffs. The habitable area for eighteen hundred souls, if souls one believes in, was delimited by the eight-hundred-meter drop to the ravine. The Attinà waterfall, which separated Santa Chionia from the Bova road, had once crashed into the silver bed of the Amendolea River below. These days the Amendolea was a damp thread persevering through a rocky wash gorge whose immediate appeal must have been most obvious to aspiring suicides.

That anyone had chosen to try to live there—it was insane.

In my capacity as a nursery school teacher whose main purview here in Santa Chionia was to reduce its abysmal child mortality rate, my bleak first thought was that geography might play an irreversible role in those statistics. How the devil did mothers teach their toddlers not to tumble over the side?

I have always lived for the feeling of being overmatched by circumstance.

Our party had come to a standstill when we rounded the bend and Santa Chionia hove into view. I was aware that my native companions were no less awestruck.

“I—I almost can’t see it,” I managed. “It’s so—it’s so bright it disappears.”

“That’s the light of the Aspromonte,” the doctor said, and the nuns murmured in agreement, “La luce dell’Aspromonte.”

Three hours earlier, when we had set out from the doctor’s house in Bova, I had watched this double-chinned and soft-fingered intellectual strap a rifle over his shoulder.

“There are wolves in the mountains,” he’d explained, blasé. “You must never go out walking except in broad daylight, and never alone.”

I had spent the plodding hours as we’d crested the foothills pondering whether the wolves had been a metaphor.

The wind cut past my ears so that all I could hear was its echo, like listening to the sea in a conch shell, but when it dropped away I caught the keen of women’s voices, a lament in a minor key.

“That singing. Is it a funeral?”

“The beating of the broom plants,” Sister Grazia replied. “Down in the riverbed—it is difficult labor. The women sing to make the day go faster.”

I could see no women, only hear their eerie chant, and I had no idea what broom plants were. My mouth was dry of words.

I had to swallow my vertigo as we entered the paese. A concrete bridge broached the plummeting Attinà waterfall, connecting the donkey path from Bova to the escarpment of Santa Chionia’s southeast wall.

“Built by an architect from Rome,” the doctor told me. “Until 1955 there was no bridge here.”

Sister Grazia added, “Just a plank of wood for the shepherds to get their goats across.”

“A plank of wood?” Even the concrete beneath my feet seemed too flimsy to fight the gravity. “Did no one ever fall?”

The doctor and the nuns laughed out loud this time. “Of course they fell,” chirped Sister Maria. “How could they not?”

Six weeks and five days later, when the October rains had finally stopped, the first person to visit our dreary prison was Cicca’s evil neighbor, Mela, with the news that the Bova bridge had been destroyed by the flooded cataract. Now that single access point that had once connected Santa Chionia to the rest of the human world was an eight-foot stretch of watery head-smashing death.

Desperate to stretch my legs, or perhaps to relish the absurdity of my new challenges, I skidded down the muddied marble of via Sant’Orsola, the village’s main “street,” an accordion of steps that fanned through the center of town down to the destruction of the piazza. I followed the city wall east, past the gap the landslide had blasted through the stonework. I stopped to stare at the void in respectful alarm—from a safe distance, behind the surviving northwest corner of what had once been the post office. Under that pile of mortar not ten feet from my saddle shoes, unbeknownst to me, lay the skeleton that would haunt me for the rest of my tenure in Santa Chionia—really, for the rest of my life. At the time, in my innocence, I thought the worst thing I had to worry about was whether the damage to the piazza would prevent me from opening my nursery school on time.

My nursery school building, directly across from the post office, was untouched—a miracle for which I was grateful. The same could not be said for many of the buildings in the stooping cavelike slums of the lower alleys. I followed via Odisseo toward the exploded masonry that had once been the Bova bridge and gawped at the empty space over which I had so recently, so hubristically, walked.

There was no way in or out of Santa Chionia anymore, thanks to the flood. Or, more accurately, thanks to a century of state neglect. It was 1960, and in Rome the Italian Space Research Council was developing a satellite to launch into orbit; meanwhile the Chionoti had no plumbing, no school, no road to connect them to opportunity.

I stared at the rushing waterfall, thinking of civilization so impossibly far away.

I was trapped in Santa Chionia, but there was nowhere in the world I was more needed. So I concluded without a self-preserving modicum of irony. After all, what is altruism but egotism?

It is hard, writing this, to resist sugarcoating my youthful self ’s naivete. But it does neither you nor me any good to pretend that I was prepared for that skeleton.

“The bridge to Bova is out, you know,” Dottor Teodoro Iiriti said when he arrived at the rectory for our weekly lunch. “A damned inconvenience. I had to drive all the way to Roccaforte and walk.”

That would have been two hours of climbing through the gorge. The doctor’s portliness didn’t suggest an athletic constitution, but everyone I ever met in the Aspromonte was a “walker,” to use their terminology. An American might have said “mountaineer.”

“And then the mayor dragged me down to look at that skeleton so I can write up a medical certificate for the police report.”

“Lucky you were here.” Don Pantaleone Bianco, the parish priest, gestured to a chair and the doctor settled his bulk into it. “Otherwise who would have done it?”

The doctor and the priest were the two men responsible for my being in Santa Chionia. In September 1959, Dottor Iiriti had attended a benefit gala in Rome, where he met my boss, Sabrina Mento. One of those fateful rapturous conversations of mutual assurances had ensued. The doctor pressed his friend Don Pantaleone to put together the formal petition requesting the installation of a Child Rescue nursery school. One year later, here I was.

At the priest’s urging, I took my usual seat. “Cicca told me it floods like this every year?”

“Well, this year was worse than most,” Don Pantaleone said. “Not the worst!”

“Not the worst,” the priest conceded. “Nineteen fifty-four was very bad, and of course 1951. That was the year Africo and Casalinuovo were destroyed.”

Dottor Iiriti held up a warning finger. “Excuse me. The towns were not destroyed. That is propaganda. They were abandoned.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Lost Boy of Santa Chionia by Juliet Grames, published by Knopf, an imprint of the Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Bear One Holdings, LLC.