ST IVES, ENGLAND — For Ithell Colquhoun, the world was alive. Energies, mythical forces, and solar alignments imbued landscapes with powers that wove together human beings, ecologies, and the cosmos, and those energies ran close to the surface in West Cornwall. It was here, therefore, that she chose to settle in her later years, with a small studio only a few miles from where Tate St Ives now stands. After her death, her archive was spread between the Tate and the National Trust, and her reputation dwindled. In recent years, however, her papers have been reunited and examined for the first time, resulting in the largest ever exhibition of Colquhoun’s strange and experimental work.

The featured artwork of this exhibition is the painting “Scylla (méditerranée)” (1938), in which a pair of fleshy rock formations emerge from clear water, with a clump of hair-like seaweed nestled in the cleft at their bases. The wall text quotes Colquhoun, who stated that the work “was suggested by what I could see of myself in a bath.” With this explanation, the image resolves into clarity and then back into uncertainty. The work is replete with associations: Eroded cliffs are female legs, but they also resemble a pair of phalluses. A sharp-ended boat sails towards the vaginal opening between them, simultaneously smooth and violent. For Colquhoun, the work was a Surrealist-inspired “double-image in the Daliesque sense,” in which the viewer sees multiple things at once.

The landscape in “Scylla (méditerranée)” is alive in a way that speaks to Colquhoun’s beliefs as an occultist, embracing and reviving ancient philosophical practices surrounding animism, mysticism, alchemy, and ritual. Here, as elsewhere, she combined these ideas with her interest in Surrealism and connected techniques such as automatic drawing and decalcomania, which involves applying blobs of paint and pressing them down with paper, before “reading” the resulting textures and patterns as if divining tea leaves.

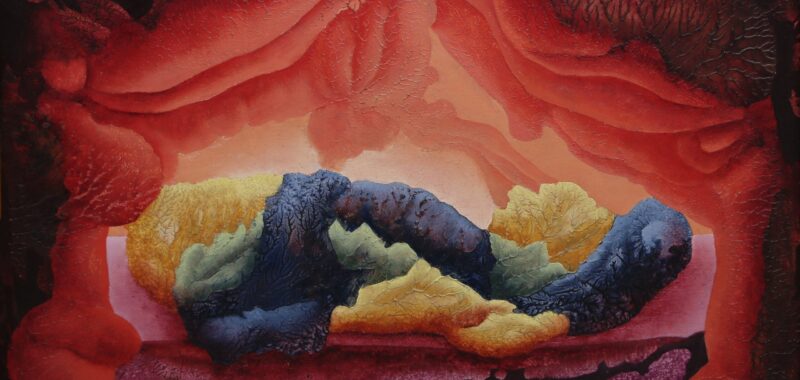

For the first time, some of Colquhoun’s decalcomania paintings are presented alongside the counterpart pages she used to press the paint down, providing an intriguing insight into her process. In “Attributes of the Moon” (1947), Colquhoun coaxes the textural forms into a goddess figure enclosed in a womb-like pink cave, treading upon a tangle of vegetal roots and an upturned crescent moon. It speaks to a spirituality that transcends any specific culture, instead drawing on a perennial understanding of the sacred that was popular among Colquhoun’s contemporaries, such as Max Ernst and Leonora Carrington.

The range of Colquhoun’s spiritual interests is confirmed in a display of personal sketches exploring everything from theoretical spatial diagrams depicting extra dimensions and the Kabbalistic tree of life, to chakras and the conjunction of masculine and feminine energies. One particularly interesting tiny sketch shows the intertwined bodies of two female lovers, one in blue and one in red ink, suggesting the union of gendered energies even in homosexual encounters.

The exhibition reaches its pinnacle in a room dedicated to Colquhoun’s paintings of ancient stone formations, including several in the nearby Cornish countryside. “The Sunset Birth” (c. 1942) is an extraordinary depiction of a local stone pierced with a hole, through which people would climb in a fertility rite. In Colquhoun’s painting, the stones appear to glow from within, encircled by colorful energy lines rooted in the depths of the translucent earth. It is a strange but compellingly confident image, full of a magic that Colquhoun felt deeply herself. It is to the credit of this generous and expansive exhibition that it offers space for Colquhoun’s works to sing in all their strangeness — and all their unidentifiable power.

Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds continues at Tate St Ives (Porthmeor Beach, Saint Ives, United Kingdom) through May 5, before traveling to Tate Britain, London, from June through October. The exhibition was curated by Katy Norris with Emma Sharples in consultation with Amy Hale, Alyce Mahon, and Richard Shillitoe.