For the next four weeks, Literary Hub will be going beyond the memes for an in-depth look at the everyday issues affecting Americans as they head to the polls on November 5th. Each week at Lit Hub we’ll be featuring reading lists, essays, and interviews on important topics like Income Inequality, Climate Justice, LGBTQ Rights, Reproductive Rights, and more. For a better handle on the issues affecting you and your loved ones—regardless of who ends up president on November 6th (or 7th, or 8th, or whenever)—stay tuned to LitHub.com in October.

Article continues after advertisement

Up first, we’ve gathered the best stories published at Lit Hub about one of the most important issues affecting Americans, income inequality, with an introduction from Alissa Quart, executive director of the non-profit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project, and author of Bootstrapped.

_______________________

On the Pernicious Myth of the Deserving Rich

by Alissa Quart

Why do so few politicians challenge the pernicious myth of the deserving rich? I have always wondered this… (I even wrote a book about it). I mean, how can it not be politically animating that CEOs make nearly 200 times more than other workers? And that all billionaires under 30 have inherited their wealth? Leaning into these two themes feels like a political no-brainer.

That’s why this year’s Democratic National Convention seemed to be onto something, with its theme of “freedom.” “Freedom” is a more compelling value than the usual “opportunity,” which is a framework I’ve always disliked intensely: opportunity smacks of individualism and finger-pointing (as in: “Why have you not grabbed your opportunity?”). For most people facing economic struggle, one reaction to the “opportunity” schema is alienation. Favorably, there seemed to be more pride than shame and anomie in popular election rhetoric, from Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez trumpeting her origins as a bartender, to Kamala Harris herself recounting her childhood as the just-middle-class daughter of a single mother in Oakland.

Still, the Democrats’ efforts haven’t gone far enough. The emphatically pro-worker Bernie Sanders and UAW President Shawn Fain don’t tend to find ideological company among the party’s venture capitalists and proud, self-proclaimed billionaires. And while both parties engage in a theater of the working-class—call it “class kitsch”—average people are often excluded from positions of political power, including among the Democrats, appearing often as props in a performance of populism.

But freedom also means economic freedom. The party still must convince us that its concept of liberation also means not having educational or medical debt or being able to afford your child’s favorite meal on your paycheck. It’s hard to feel free when you’re working contingently and living in a city with sky-high rents. When politicians sidestep these issues, they give the impression that they accept the notion that some people will always be poor—that is, having no “freedom” from exploitation.

As I wrote in my last book Bootstrapped, we can learn from the New Deal 1930s. The way Democrats talked then was much clearer, for example identifying opposing groups like “the workers” and “the bosses.” When the New Deal coalition collapsed in the 1970s, neoliberals took their place. For nearly fifty years, they have made believe that there are no sides—no “bosses” and “workers,” only those who grabbed opportunity and those who didn’t—all while adopting increasingly right–wing talking points about the economy. They don’t tend to mention high quality job creation or raising the minimum wage. And this political ambiguity, political expert Anat Shenker-Osorio tells me, has put Democrats in a “super messy narrative space,” which isn’t good for voters.

Democrats may not have found the needed state of clarity. But they have gotten marginally more comfortable with the language of class, even if their policy priorities are lagging and the workers themselves too rarely speak. This increased focus on social class creates an opening that we would do well to take advantage of. We should free ourselves of the murky Democratic economic storylines of the last thirty years, including the “opportunity” storyline, and return to messaging that is more high-contrast and worker-centered, expressed as often as possible by the workers themselves. Democrats might find that social-class-rage is an underutilized energy source.

_______________________

The 10 Best Books for Understanding American Class

While most Americans like to believe they live in a meritocracy, in which one can bootstrap from the assembly line to the board room with nothing more than moxie and a dream, that is not really the case. The following books unpack the hard realities of an American class system as entrenched as the 18th-century aristocracy the Founders so famously rejected.

“Those Folks Never Had Their Lights Turned Off.” On the Literary Importance of Highlighting the Haves and the Have-Nots

Since reading Naomi Kanakia’s essay, “Contemporary Literary Novels Are Haunted by the Absence of Money,” I’ve been recalling how often, nearly fifty years ago, Ray Carver and I complained about the same issue. At one point in our lives, we lived next to one another in dumpy motel cabins near Iowa City that rented for $10 a night. We regularly loaned each other a ten-dollar bill to avoid eviction.

Ray said more than once in those days, “Someday, I’m going to write a story, Without a Dime.” He’d gesture toward an old movie on TV and say: “Those folks never had their lights turned off. You won’t catch them running out of TP.” He tossed out similar comments about writers, no matter how much he loved what they wrote (and he did)—John Cheever, Ann Beattie, John Updike—also the postmodernists who then dominated the literary scene—Thomas Pynchon, John Barth, Robert Coover. “Nobody’s getting evicted in their stories. No cars get repossessed.”

Poverty Hurts Children in Ways We’re Just Beginning to Understand

Until recently, analysts, policymakers, and many of the rest of us thought the pronounced difficulties poor children face were the result of factors like single-parent families, bad prenatal health, poor nutrition, low levels of parental education, poor schools, crime-ridden neighborhoods, and frequent moving and evictions.This remains true. Recent research, however, has increasingly shown that low income itself is a key, and arguably the major, cause of the debilitating outcomes in cognition, emotional stability, and health for poor children. The countless studies reinforcing this claim are an important breakthrough.

The claim that poverty-level income explains many of the damaging hardships for children had long been challenged both by the political right and some mainstream analysts, but the impressive newer research has whittled away at these counterclaims. The new emphasis on the importance of money alone leads to proposed solutions that are more efficient at reducing poverty, the most effective of which, in my view and that of a growing number of academic experts, is an unconditional cash allowance for households with children.

Americans Are Right To Think the Economy Is Rigged

America’s proudest boast throughout history has been that we have no class system, and that opportunity is available to all.

Yet a starting point in an exploration of our nation must be to acknowledge that today we do have a class hierarchy, and the Greens and the Knapps are on the bottom tier. Billionaires like Jeff Bezos are the new American aristocrats, while people like the Kristofs and WuDunns, and probably you if you’re reading this book, constitute a new privileged class. This 21st-century version of feudalism rests not only on money but also on access to education and the ability to pass down inherited benefits and values to one’s children. Children from the richest 1 percent of households are 77 times more likely to attend an Ivy League college than children from the bottom 20 percent.

Are Civilization and Income Inequality Inextricably Intertwined?

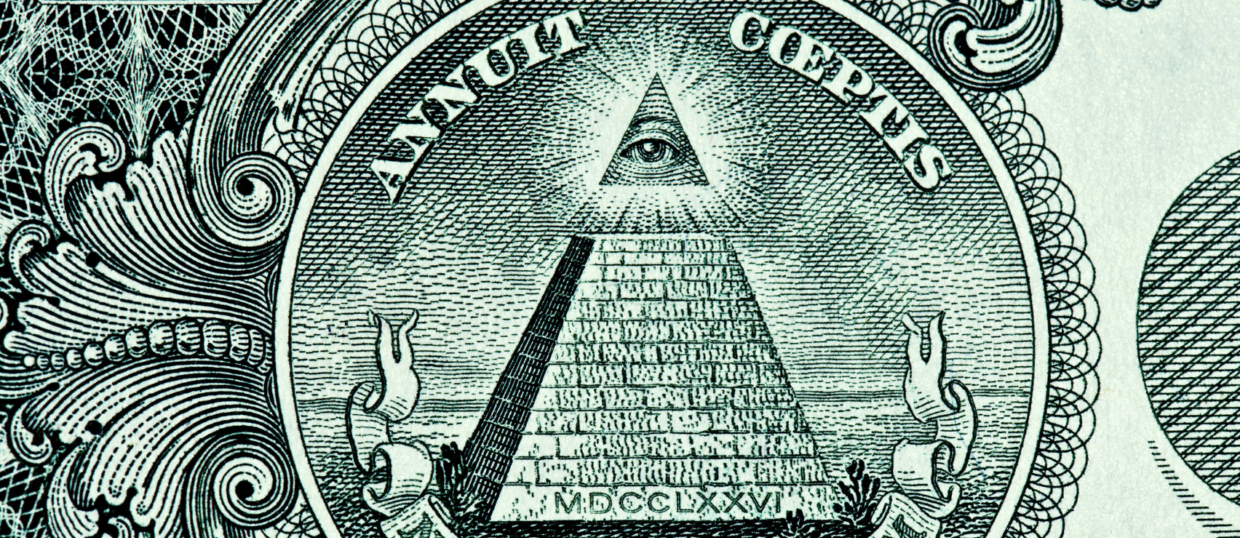

The more we understand what human life was like before agriculture, the more civilization looks like a pyramid scheme. Disparities of wealth and power were among the first things to emerge when people settled into villages and towns. Someone had to make decisions about who got how much of what, and when. Someone had to organize the sowing and the reaping, the protection and trading of land and livestock. Once wealth emerged, so did an elite class that was naturally tempted to benefit further from their privileged position.

When similar situations arise in foraging societies—when a large animal is killed, for example—we’ve seen how formal codes of behavior kick in to prevent inequities in the distribution of the windfall. Among bands of a few dozen foragers who all know each other intimately, cheating is quickly detected and discouraged—initially with lighthearted humor, but with the serious threat of more severe repercussions if a light ribbing proves ineffective. Once human communities grew beyond the point where every individual had a direct relationship with everyone else, something fascinating and terrible happened: other people became abstractions. Perhaps Joseph Stalin was thinking along these lines when he said, “one death is a tragedy; a million is a statistic.”

Who Are the 9.9 Percent? A Closer Look at the Math of American Inequality

When you are not rich, you are quite sure you know what it would feel like to be rich. Once you become rich, you are not so sure. You come to see that there are many people much richer than you, and you can’t help but wonder what it would be like to be them. This was one of the thoughts I picked up from Grandfather, rather indirectly, when he complained, as he often did, of the monstrous injustice of the estate tax.

The government, I learned early, taxed away three quarters of the Colonel’s fortune upon his death. The remaining quarter was divided among four siblings. Thus, the Colonel at death must have been worth an impressive sixteen times more than Grandfather at his peak, or so I calculated with my sixth-grade math skills. I thought this might explain some of the deference—or was it fear?—that crept around the edges of Grandfather’s voice when the subject turned to the Colonel. I wondered if it also explained the occasional outbursts of hostility that Grandfather directed at the Rockefellers. They must have been worth sixteen times more than the Colonel, or maybe much more.

As Much Power As the President: How Billionaires Became More Influential than World Leaders

Broadly, an observer of the economy can make out a number of social and economic levels, based not only on how much money people have but how they make their living. This book has so far covered the economics of the richest households, whose members may work, and often earn gigantic CEO incomes from managing large corporate entities.

But primarily the household incomes of these families are made up of income from property—dividends on stocks, rent on residential or commercial properties, interest income from big cash deposits, and capital gains from corporate stock buybacks.