LOS ANGELES — Aliza Nisenbaum’s current exhibition at Regen Projects, her first with the gallery, extends her career-long project of depicting the denizens of Latino and other micro-communities at home and at work — in this case, the city’s dance troupes. The Mexico-born Nisenbaum spent time in Los Angeles during the COVID-19 lockdowns, meeting luminaries Teresita de Jesús of Studio 10, Folklorico Revolución, Mariachi Tierra Mia, and Amelia Muñoz Dancers through connections in the dance scene in New York, where she is based. She began to paint them and returned to their studios in 2023 to photograph them as they danced, dressed, and rested behind the scenes. Nisenbaum brings her earlier interest in abstraction with her in depicting her subjects, creating colorful patterned environments for her dancers in which solid floors and walls bend and dissolve as if moved by the force of an unheard mariachi band.

At the entrance to the show is a bust-length portrait of a woman with a serious expression who raises a lit candle to her head. Titled “Balance” (all works 2024), it refers to la Bruja, a specific dance originating in Veracruz, where tradition had it that women would carry breakfast to their fishermen husbands in the early morning darkness while balancing candles on their heads. Supposedly, the women looked as if they were floating, conjuring the image of a bruja, or witch, which could be diabolical or liberated, depending on your point of view. A large tableau by Nisenbaum called “La Bruja” shows a group of women practicing the dance, some gazing into mirrors and raising their diaphanous lace skirts to pose. In these paintings, we are hard-pressed to define the contours of the room in which we find ourselves. A turquoise-and-white-tiled floor undulates beneath the women, the mirror baffles solidity, and an overall brilliantly colored palette in skin tones fractures the certainties of skin and bones.

Some of the dancers showed up at the public opening wearing the same costumes as seen in the paintings: This finery is their own handiwork, and Nisenbaum lovingly depicts it with equal care. (The dancers also returned for a performance and special opening mounted just for them, a tradition the artist implements whenever possible.) In “Atanera, Preciosa y Orgullosa” (Haughty, Gorgeous and Proud, also the title of the exhibition) for instance, four women and a young girl form a dynamic pyramidal composition in their dresses of bright green and purple striped with rainbow colors. High-tops are cast aside on a patterned rug as they pull on special red dancing shoes. In “Extension de Brazos,” the Bruja dancers spread their lacy skirts wide, the foremost figure casting an ample shadow whose color gradation creates a kind of visual wobble that mimics the movement of huapango rhythms.

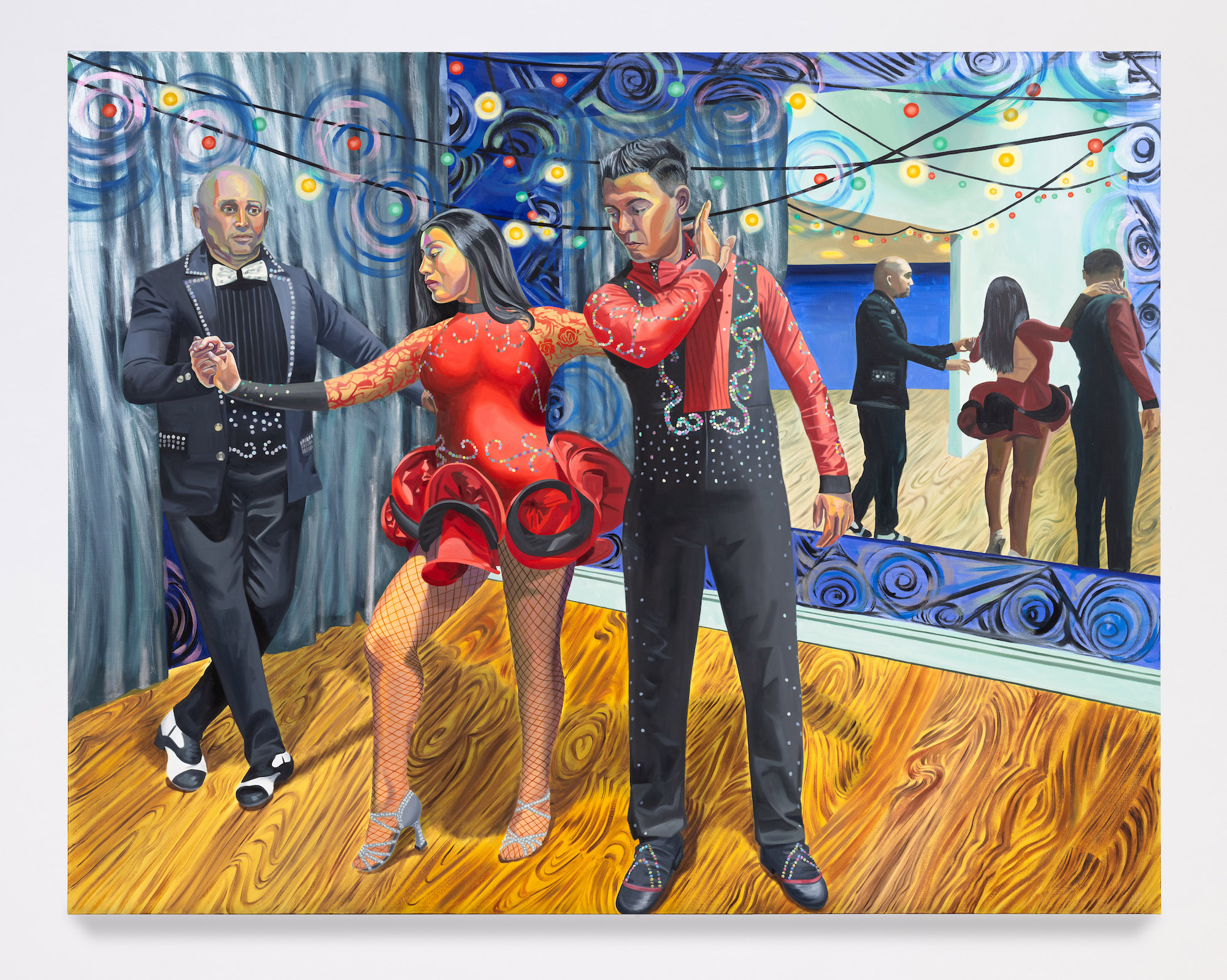

Nisenbaum takes a new direction in “Shine Arm Styling on 1,” in which a male and female dancer, the latter in a brilliant red tutu, are surrounded by barres placed askew, confusing the space. In the background somewhere, a separate group rehearses, and to either side, sketchy blue outlines of dancers imply the promise or memory of other participants. This kind of figural dissolution seems reminiscent of early paintings by David Salle, but nowhere does one sense the alienation of an earlier postmodern condition. Instead, Nisenbaum’s socially engaged projects are very much about the communities in which she embeds herself, and her portraiture belongs to a wave of painters for whom the genre offers new possibilities of representation in an expanded canon.

Aliza Nisenbaum: Altanera, Preciosa y Orgullosa continues at Regen Projects (6750 Santa Monica Boulevard, Los Angeles) through October 26. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.