It is the first week of April, Paris, 1979. You arrive at noon in Montparnasse, the address you’d been given, and ring the buzzer. You’re let in and climb several flights of stairs, until you reach the apartment where Sophie Calle greets you. A friend of a friend, she had called you last week, inviting you to sleep in her bed. From April 1 at 5 p.m. to April 9 at 10 a.m., Calle has arranged for a series of sleepers to take turns in her bed. You agree to be one of them.

Article continues after advertisement

Her instructions are simple: she will provide clean bedding and breakfast, lunch, or dinner; she will record the answers you will give to a questionnaire she’s prepared, not to pry, but to establish a “neutral” relationship; and most strangely, she will photograph you every hour. She’ll watch you sleep.

By the end of your eight-hour stay, you will have become one of the twenty-seven “sleepers” that make up The Sleepers (Les dormeurs), Calle’s first exhibition, which debuted in 1979. Most of the sleepers are acquaintances or strangers, and the project was not planned as an exhibition—it began as a singular exploration of encounter and photography.

As Calle explains, “For The Sleepers, I invited a woman I bumped into at the market in Rue Daguerre to come and sleep in my bed…She was living with Bernard Lamarche-Vadel, the art critic. He asked if he could see the photos and then he came up with the idea of exhibiting them at the Biennale des jeunes [Young Artists’ Biennial] in Paris. I remember at the time asking myself: ‘Do I want to be an artist?’”

Like the sleepers themselves, Calle’s narratives reveal and occlude, beckon and turn away.

Calle’s path to The Sleepers and her artistic career was unconventional. At 18, she traveled to Lebanon to understand the Palestinian struggle (and to impress a leftist leader she had fallen in love with), returning to Paris to work with the Prison Information Group and help organize illegal abortions in the early 1970s. As a sociology student at the University of Paris IX, she studied under Jean Baudrillard, who would later write an essay for her first book, Suite Vénitienne (1983).

Rather than complete her degree, Calle embarked on a seven-year journey across Crete, Mexico, Canada, and the United States. It was in Bolinas, California, watching images emerge in a rented house’s darkroom, that she decided to return to Paris and pursue photography. Back in the city at 26, she lived between her father’s apartment—where The Sleepers would be staged—and an abandoned hotel at Gare d’Orsay, where she photographed empty rooms and gathered discarded objects.

During this time, she also secretly followed a man through Venice, documenting the experience in what would become Suite Vénitienne (1983) and, following The Sleepers, embarked on her second exhibition. For this piece she invited passers-by in the Bronx to take her wherever they wanted, preferably to a place they could never forget, pinning the resulting photos and companion texts, taken from interviews with her guides to the gallery walls. This early work is haunted by transience, eschewing prepackaged narratives to trace fluctuations of intimacy and distance. It also laid the foundations for Calle’s process: in almost all cases, she follows a set of protocols, creating a “game” she records through image and text that become exhibitions, artist’s books, or both.

In the 1980s, Calle expanded on her experiments in works like The Hotel (1981), where she took a job as a chambermaid at a luxury hotel in Venice and secretly documented the guests using a hidden camera and tape recorder. The line between personal observation and art was once again blurred as Calle became part of the world she was chronicling.

Later projects like Take Care of Yourself (2007), in which Calle invited 107 women to interpret a breakup letter she had received via email, continued her exploration of narrative and identity. The women’s interpretations—ranging from the poetic to the analytical, depending on their professions—reveal the powerful role systems of discourse play in shaping even the most intimate experiences.

Although created before Calle defined herself as an artist, The Sleepers has remained central to her oeuvre. She included photos and captions from the original exhibition in M’as-tu vue, her 2003 retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, and features them in Overshare, the first North American survey of her work, now on view at the Walker Art Center. In 2000, Actes Sud produced the piece as a book in French, incorporating a novella-like text, which includes Calle’s impressions as well as transcriptions from the tape recordings she made of answers to the questionnaire, sometimes leaving the tape running, her subjects unaware. Siglio Press has newly released the project as an artist’s book, translated by Emma Ramadan.

This tactile, luxurious edition features navy cloth binding—slightly satiny and plush—silver-stamped lettering, and silver gilded edges. The book rests in the hands with the weight of an album and the intimacy of diary. How can an object be so soft to the touch but also metallic, shining?

Like the sleepers themselves, Calle’s narratives reveal and occlude, beckon and turn away. There’s a choreography to this. Chapters are organized by sleeper, titled with the person’s name and the order in which they come to sleep. Each written account begins with Calle’s connection to the sleeper and their agreement to participate. Calle then relays their answers to her questionnaire, condensing into summary or using direct quotes. The questions, set in italics, use the distancing third person and range from the mundane (“Name, age, profession?”) to the brash (“Does he/she ever pee bed?”) to the provocatively worded (“What are his/her motives for agreeing to come sleep?”).

When I asked Emma Ramadan about the word “motives,” she pointed to the precision of Calle’s word choice: “motives isn’t a mistranslation of the word for ‘reasons,’ because Calle uses that word in a different context.” Calle’s word choice purposefully shifts “attention away from the brazenness of taking photos of strangers in their sleep and onto the bizarreness of the strangers who said yes.”

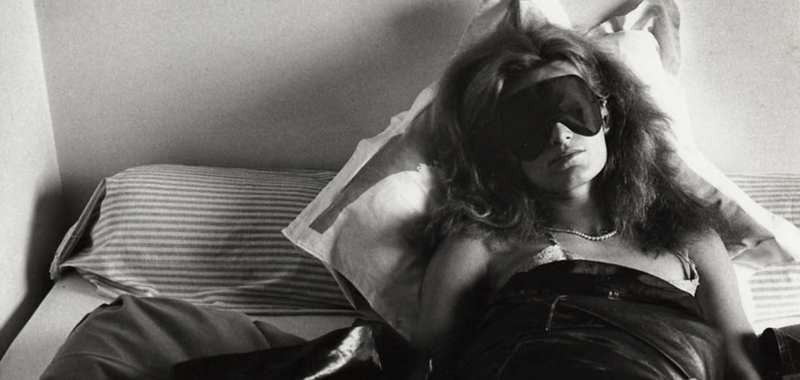

Following each narrative are several black-and-white photographs of the sleeper in bed, stacked two to a page and accompanied by captions excerpted from the preceding text. Calle takes a turn sleeping when there is a gap in participants and marks this by a photograph of the empty bed. When I suggest to Calle that, since she had been one of the sleepers, she might like to answer the questionnaire now, after the fact, she declines, reasserting the purpose of the exchange, which was to establish contact with each sleeper, adding, “since I didn’t want this contact to become familiar I made a questionnaire in order to have a neutral contact.”

While the book’s text combines the exposé with the sociologists’ report, the photographs tell an intimate story. Pulled in close, they capture sleep’s rumpled sheets and contorted positions. A foot, naked buttocks, and tousled hair appear alongside wakeful moments of quiet reflection or animated discussion. The last photo of the fourth sleeper, Rachel Sindler, who is Calle’s mother, shows her regal profile as she reclines in a flower-printed robe, glass of champagne in hand. In the image above, Sindler lies on her side, arm wrapped protectively around herself, gazing directly into the camera with a soft smile.

Unlike most photos in the book, this one lacks a caption. Its silence, combined with Calle’s subtle self-presence—like the pillowcase printed with a sleeping silhouette that appears in many of the photographs—heightens the intimacy, the mystery, the trace. Most of the sleepers will never again appear in Calle’s work and foretell the many strangers who will flow through her projects, but she will revisit her mother as a subject several times, most notably in Couldn’t Catch Death, a film installation created on her mother’s deathbed and shown at the 2007 Venice Biennale.

The vulnerability of her subjects, which Calle captures so unflinchingly, raises profound philosophical questions: Who are we when we are most unaware? What happens when we are asleep? While everyone sleeps, sleep has long been linked to passivity and femininity in art, inspiring works like Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (1508). This tension between activity and passivity is particularly poignant when it comes to Calle’s female sleepers, and the gender dynamics of the work offer a prescient commentary. A bed is never just a bed, and an encounter is never just an encounter.

Of the twenty-seven participants, a stark imbalance is telling: only eight women participate, and all but two knew Calle personally. One of the female strangers comes with a mutual friend. When the other female stranger, called “X,” hired through a babysitting service, discovers she’s meant to sleep rather than babysit, she becomes agitated. Only after receiving her fiancé’s telephone blessing does she relax, getting “under the sheets, dressed, without my asking her to.” Her comment— “No one ever photographs her”—surfaces the way many women navigate visibility, requiring permission to be seen.

The imperative repeatedly expressed across Calle’s projects speaks directly to our moment: the art of seeing and of being seen must also address freedom and agency.

The nineteen male participants, by contrast, demonstrate a striking confidence. Thirteen are complete strangers to Calle, yet they display an unsettling comfort with crossing boundaries. The ninth sleeper suggests Calle join him in bed; when she doesn’t respond, her silence becomes a pointed commentary on masculine presumption. She later has a little fun at his expense, putting on a “small starched white pinafore” when he says, “the situation resembles a doctor-patient relationship.”

Another male sleeper (also a stranger) tells her about a recurring dream of “a woman lying down, naked, on a marble floor, like in a hotel lobby. A cadaver in a morgue. Around her, a swarm of bees, the bees enter the woman’s vagina one by one.” When the last two sleepers, a pair, are asked, “Do they regret coming?” Calle writes, “They’ll let me know tomorrow, because what if someone comes in to kill them and writes ‘pigs’ on the walls…” recalling the Tate-LaBianca murders from a decade before.

While Calle appears to hold control as the photographer, the gendered responses of her subjects divulge the dynamics of who truly feels entitled to occupy space, to be seen, to make demands. While most of the photos show only the cracked wall behind Calle’s bed, some reveal that, a little higher up, she has pinned postcards of reclining nudes, including Ingres’ Grande Odalisque (1814)—a traditional emblem of the passive female subject. These glimpses of juxtaposition, where messy life meets the art historical project of the reclining female nude, spark with Calle’s intervention. This connection between art and life is underscored as her female subjects actively negotiate their visibility while her male subjects’ unearned confidence becomes its own kind of exposure.

The Sleepers navigates these tensions with joie de vivre, but two other works initiated during this period resonate with subtle, darker tones. In one, an entry in Calle’s diary later shown at her Centre Pompidou retrospective, she photographed a blood-soaked bed with the simple caption: “Period du 1st avril au 9 avril. Le lit. It is important to have a good sleep.” The year of the diary is not disclosed, but the days and month exactly overlap with The Sleepers, and the dairy’s lonely, gruesome bed sharply contrasts the artwork’s warm, communal images.

In another, reproduced in True Stories, a photograph taken from the upper story of a building looks down on a mattress and other trash. This had been Calle’s bed, where she slept until the age of seventeen. “Then my mother put it in a room she rented out. On October 7, 1979, the tenant lay down on it and set himself on fire. He died. The firemen threw the bed out the window. It was there, in the courtyard of the building, for nine days.” Placing these works alongside Calle’s early pieces on transience troubles easy oppositions of home and homelessness by disclosing the way domestic spaces of intimacy and rest can become sites of exposure, violence, and, perhaps, transformation.

In our digital age Calle’s themes take on new urgency. While Calle’s sleepers could choose when to leave her bed and her camera’s gaze, we now live in a state of perpetual documentation—through social media, facial recognition software, and corporate data collection. And in May 2024, the number of forcibly displaced people has reached 120 million, adding further gravity to transience, precarity, and the condition of being tracked. The themes Calle has explored have amplified into a chronic condition of surveillance and hyper-vulnerability. Through this lens, the imperative repeatedly expressed across Calle’s projects speaks directly to our moment: the art of seeing and of being seen must also address freedom and agency.