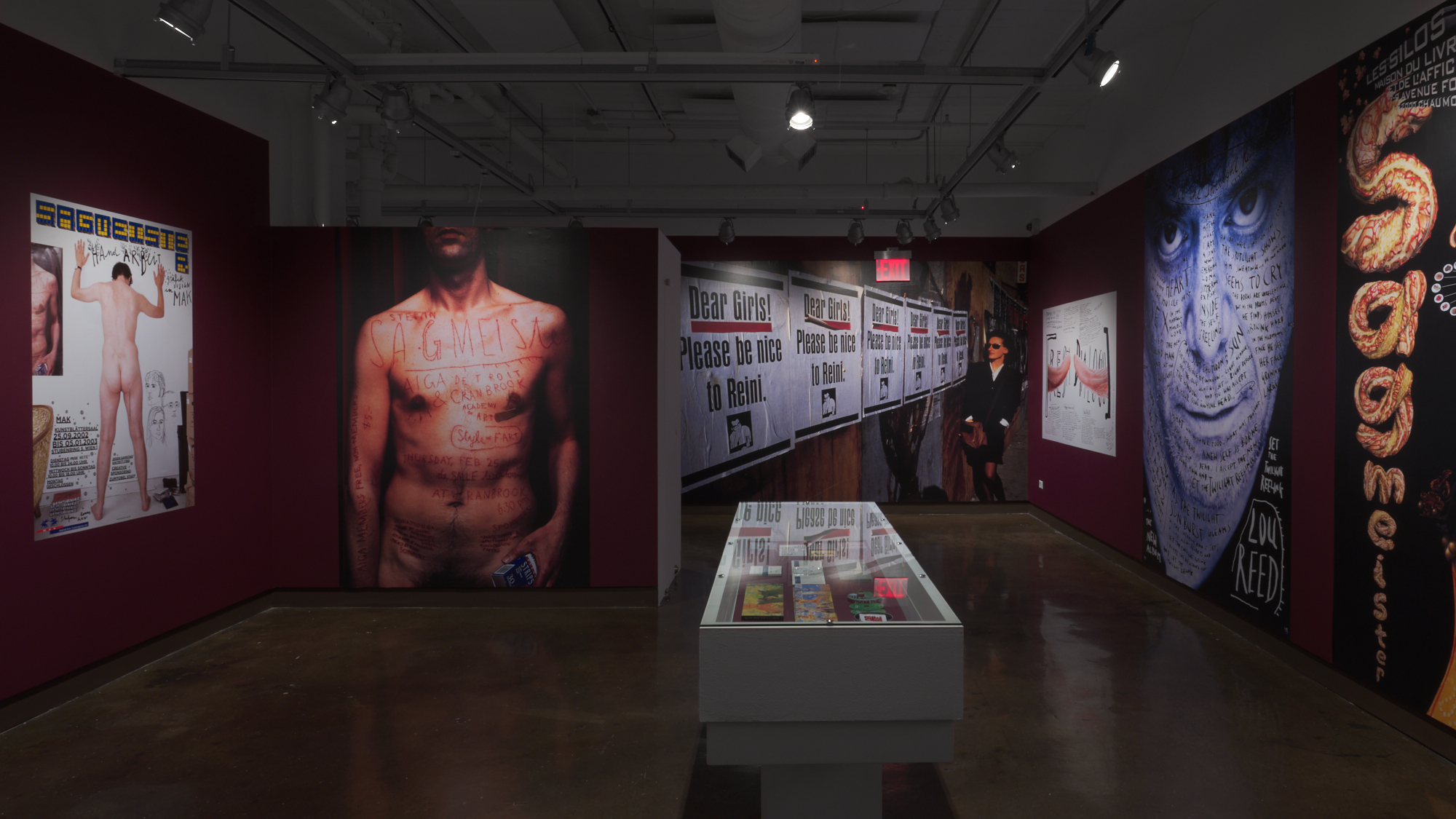

One of the leading graphic designers of his generation, Stefan Sagmeister has been influencing the field since the early 1990s. Now he’s having a retrospective at the School of Visual Arts, a leading school for generations of graphic designers and artists who continue to push the boundaries of art and design in media, and culture in general. He’s also the subject of the current Masters Series award and exhibition, which is slated to close on October 12.

He first established himself as part of Leo Burnett’s Hong Kong Design Group before joining the influential studio of the late, great Tibor Kalman. In 1993, he launched his own studio, and went on to create distinctive designs for a wide range of brands and bands, including The Rolling Stones, David Byrne, HBO, and the Guggenheim Museum. He even won a Grammy Award in 2005 for art directing the box set of Once in a Lifetime by Talking Heads.

More recently, he’s been venturing into contemporary art. He finds antique Central European paintings — mostly German or Austrian and of negligible art historical significance — which he transforms with colorful resin, turning them into curious objects that look thoroughly contemporary but are also in dialogue with a mysterious past.

We sat down to talk about his 30 years of design, his viral TED talk about sabbaticals — which he highly recommends — why our world is dominated by pessimism, and why he refuses to succumb to the media-induced urge to be negative.

Hyperallergic: I always find that retrospectives help people reflect on their ideas of what history is. So I’m curious, what are your ideas around history? Because some of your work reconfigures historic artworks, so how would you describe your relationship with the notion of history?

Stefan Sagmeister: I have a very, very, very tight relationship to history because I would say the whole last five years, all the work that I’ve been involved in had something to do with long-term thinking, particularly these insights that I had, that they really are two completely different views of the world or of human development. One is short-term, like all media, social and traditional looks at it, the other one is long-term, and we, of course, are surrounded by short-term messages.

For me, just unbelievably surprising was that if I look at everything from the long-term, it’s the exact 180-degree opposite point of view on almost any area of human development. The subject came up to me when I was at the American Academy in Rome, and this dinner companion, they have great dinners there every night, told me that what we are seeing now in Poland, Brazil, and Turkey really means the end of modern democracy, which was interesting until I looked it up.

This was five years ago, and if you look at modern democracy [and] when it started with the foundation of the United States until now, at that point[, meaning five years ago,] we were very, very close to the absolute, most democratic moment in the history of the Earth. But because of the short-term messages, this super educated lawyer who was my dinner companion, had no idea about the world he lives in.

H: Right. So that became your Now is Better book, right?

SS: Exactly. Yes.

H: I think we both share a certain optimism, which I like about your work. I’d love your thoughts on why pessimism seems to reign in the creative fields.

SS: Because we love it.

H: Why?

SS: Because of numerous reasons. One is the amygdala in our brain, it lets negative messages in.

H: Fight or flight.

SS: Yup. True, because of our Stone Age predecessors, the people who were optimists died because life was very, very difficult. I think that’s definitely a [major] reason, and we see this, there is tons of research that proves this. I just saw one in nature very recently, that showed click-through rates on newspaper headlines depending on how many positive or negative words were used in the headlines, very simple A/B testing. The click-through rate goes down the more positive words are used, it goes up the more negative words are used. This is, of course, why all media gives us the negative stuff, and I noticed it myself. I’m the same way. I noticed it very strongly when we edited our film that’s running here. Every time I looked like a shithead, it was super interesting. Every time people said something great and positive about me, it was so boring we couldn’t use it.

H: Right. I mean, bad gossip travels, right?

SS: Absolutely.

H: Good gossip goes nowhere.

SS: Totally.

H: I’m really fascinated by that, because there seems to be no repercussions for pessimism, yet people see optimists as naive, innocent.

SS: 100%.

H: So how do you maintain your optimism?

SS: Well, it has a couple of advantages. For one, my life is much better. It’s as simple as that. Number two, I think I have a suspicion that I was born with it. I have old audio tapes that I had sent to my sister when she was in the States, and I was in Austria as an eight-year-old, that has an enthusiasm in the voice that I think I was always like that. Number three, I would say when I just look at it rationally, it makes a whole bunch of sense, because if I have a 50-50 chance to solve a problem, if I approach it positively, I might move that into a 60-40 proposition, but if I go about it negatively, I might reverse that.

So I think just from a purely rational point of view, my chances to actually solve trouble or solve challenges is 100% better.

H: Can you explain that a little more? I’m really interested in that idea.

SS: Right now, last year there was very, very good research. Looking at 100,000 young people worldwide, over half, 53% of them think that humanity will end in their lifetime. Now, these 53% are going to do nothing. They’re going to be depressed. They’re anxious. They are not going to solve global warming or the dying of the species. They’re going to sit in their room depressed. I think that you basically need, and I know it from myself, if I’m anxious and depressed, I’m not really useful to my surroundings, to my partner, to my friends, to my family, I’m much more useful when I’m in a good mood or in good shape. Going from that, if I have a problem to solve and I approach that positively, my chances improve. So overall, and of course, having then solved that problem will make me more optimistic again because I’ve just solved it.

I think that part of the reason that I’m doing this Now is Better project is to show that we have already solved a lot. Let’s say the biggest problem of our lives, global warming. It is helpful to know that when it came to acid rain, a gigantic problem on the covers of every newspaper 20 years ago, it was basically solved. Now, global warming is a more difficult thing to solve than acid rain.

H: Or the ozone layer was solved.

SS: Yes. But nevertheless, it’s quite good to be reminded of it, because as far as the newspapers are concerned, as far as the media is concerned, this was a problem. Once it was solved, it didn’t really stay news anymore.

H: Do you think it has to do with the lack of an ideology in society, wherein that we don’t all believe the same thing anymore? I wonder whether that is part of it, and what role that might play, and how you see that work in your own field, if at all?

SS: I would have to give this some more thought, meaning I think that we definitely see that to a large extent, specifically in New York City, we threw out religion without replacing certain elements that were really good about religion with something else. I think parts of them were replaced, in many ways you could say that MoMA, and the Met [Museum], and galleries are replacing some sort of contemplation possibilities that we might have had in church. Some parts of it I think are, but then some other parts.

H: Secular spirituality.

SS: Yes, but also the possibility of certain celebration, the possibility of the repetition of ideas, meaning I’m sure that we could go on, that basically we were thrown out leaving a void. What I’ve seen by looking at the past is that every development, or even every [moment of] progress comes with side effects, some of them we can know, some them, they’re completely unintended and we can’t know, and then we have to take care of the negative side effects before we can move on.

H: I was thinking about your work, and some of the words that first come to mind seem to be texture and layers. Now, how would you characterize your own work of the past 30 years, and how accurate do you think my assessment would be?

SS: If I would say 30 years, I would say one thing that was always on my mind was somehow trying to touch the viewer emotionally. I grew up when modernism reigned, quite cold, very functional, and I’ve always felt that the way we communicate, be it in print, or online, or in a gallery, or on a construction site, should somehow be human. So for a long period, we made sure in the studio that the things that we made looked like a person made them, and to the point when it was appropriate, even to bring myself in so it was very clear this is a person who is speaking to you. This was not made by a machine, it doesn’t look like it was made by a machine, which very much came out of this modernism credo, like everything has to be objective, and every logo should look like it was created by a computer. Even though in real life every logo was decided upon by dozens of people.

H: So one of my favorite questions to ask designers who work with contemporary art and contemporary artists, is what is the difference between design and contemporary art?

SS: Do you have hours?

H: I think it’s one of those questions that never quite gets settled, and that’s kind of why it’s so beautiful.

SS: Well, I think at the very basic, I think the easiest one is one of function. There’s this famous Donald Judd quote, “Design has to work, art does not.” He meant that it can just be, it doesn’t have to do anything, it’s not dragged down by the necessity of function, while design, of course, needs to function. At its basic thing, I think that’s true. When you look at it really tightly it tends to fall apart because, let’s say even in the 17th century, the French king would commission tableware that was never meant to be eaten from, so it looked like tableware, it looked like plates, but they went into betweens immediately. Basically it had the aura of function, but was never meant to really be [treated] as tableware. We have a friend of mine, a fantastic designer in Holland, Hella Jongerius, who has a nice saying, “There are still people out there who can ruin a perfectly fine vase by putting flowers in it.”

Of course, if you go on, let’s say if we pick maybe the most famous artist of the 20th century, Andy Warhol, one of the two let’s say, and he, of course, started as a designer. He was a very well-known illustrator and won many awards from the New York Art Directors Club as a commercial illustrator. Then he made a conscious decision to change into fine art, but continued to do graphic design. I would argue that when he was a fine artist, and as a fine artist he designed album covers for The Velvet Underground, for The Rolling Stones, that are arguably much better quality than the fine art that he did at the same time. Meaning at the time when he did the Stones cover, Sticky Fingers, which is a fabulous piece of work, he also did stupid portraits of German industrialist wives that he really did for money, ultimately to finance his graphic design project, Interview Magazine, so it becomes very muddled.

Even better, I think my favorite example with Warhol is that he, of course, with all the other pop artists, stood in stark contrast against the Abstract Expressionists, who were basically a group of macho artists who came before them, and the pop artists were much more feminine, much gayer, very different approach, and loved commerciality. When Warhol created the Brillo Box, he didn’t just design … when he first showed it, he showed the Brillo Box, he showed the box of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, of Campbell soups, so there was a whole ton of them, but only the Brillo Box became this icon of 20th century Pop Art. Now, Warhol did not know that the Brillo Box was designed by an Abstract Expressionist painter, so somehow Abstract Expressionism kind of finagled its way back into the pop commerciality, so the whole thing really becomes odd.

I think that the best ultimate explanation that I’ve ever read comes from [Theodor] Adorno, and he says that, “Ultimately, there is no such thing as a 100% functionality, because even in the most engineered project there is even a hair of transparency also that comes from the outworld.” On the other hand, there is no such thing as a 100% percent non-functionality because, let’s say even if you stand in front of a Donald Judd, that just meant that was created just so that somebody could take a selfie in front of it, that’s functionality. He basically says, “Everything is on a sliding scale,” and that makes the most sense to me.

H: Right. Well, you mentioned a factory and a cathedral, but a cathedral sometimes has a hidden function, or an invisible function that as a society we don’t see. Absolutely.

If there are three works in your body of work that you think people should take a look at, that gives a real sense of some of the ideas at the foundation of what you do, what are those three? Or perhaps even three works you keep going back to, and continue to be rich for you?

SS: Well, I would say let’s pick one from the very early ones. I would say let’s pick a David Byrne album cover. I picked it because, from my point of view, it was a pleasure to work on. I have only good memories with it, and it was rich in the various types of feelings that it showed. I think it was a good visualization of the music, which I felt album covers should be.

Then number two, I would pick the whole series, or part of the series of Things I Have Learned in My Life So Far, simply because I think it was the first time that we, in the studio, really tried to take something, basically to use the language of design for something that is not promotional or advertising.

So we basically created projects that came out of a list in my diary, Things I Have Learned In My Life So Far was the name of that list, and I published them on billboards, on giant LED screens, in magazines, in everyday spaces. I remember first feeling that it was quite self-indulgent, and then got so much positive feedback that it made sense to continue. Then in time Instagram became big, and having life-affirming quotes on Instagram became … there was such a deluge of it that we stayed away from it again, because many things that are interesting at one point become utterly boring when they are repeated ad nauseam.

[For the third,] I would definitely pick something from the Beautiful Numbers series, meaning if it would just be a single work, let me see what’s out there. It has to be a single work or it can be a group?

H: You can decide.

SS: Yeah, then it’s just the group. I think that the idea for me to try to push this forward or to try to communicate this as a communication designer, that there is a completely different way to look at the world, I feel is what I should do now. I have nothing against commercial work. I think that by and large, right now, commercial work probably has more distribution than any other kind of work. I can get a huge kick out of the fact that the Coca-Cola branding is much better now than it was 10 years ago, because I know that an umbrella with that branding is going to be in the jungle of Borneo, and will have some sort of influence, a much bigger one than whatever MoMA is showing right now.

H: Got it. So my final question is about your infamous sabbaticals. You’re just going on one. So do you want to explain what you’ve discovered about sabbaticals? Because I’ve seen your TED talk, where you talk about the way you distribute leisure throughout your life rather than bracketing it at the end, which most people do. What have you learned from that process, and why do you think others should consider it?

SS: I think what I said in that TED Talk was basically rather than studying for 20 years, working for 40, and then retiring for 20, why don’t I take whatever five years of those retirement years, and put them in between those 30 years of work? Because, for one thing, then the work that I do in those sabbatical years has a chance to influence my working years rather than just benefiting a grandchild, but also, when I actually retire, I’d be so much better at it because I have all that much experience.

I did that TED Talk during the second sabbatical. I was actually taking time off in Indonesia to do that TED Talk, to fly to TED. Now, of course, I have much more experience because I’ve already done a third, and I’m about to go on the fourth, and I’d say that all of the stuff that I said turned out to be true, but also much more. Because of the talk, I’ve had dozens and dozens of people come up to me and say, “I’ve done a sabbatical too. I’ve seen your talk and I’ve done a sabbatical,” so of course my first question was always, “How was it?” Every single person that I talked to had sort of glossy eyes, and the phrase “the best year of my life” or

the best thing I’ve ever done” appeared a lot.

I think that from my first sabbatical I really had a big hurdle to jump over, because I thought all of our clients would leave. I thought people would think of it as very unprofessional. The [first] sabbatical was in the year 2000, which was the height of the first internet boom, so it just seemed very odd to close your successful studio then. None of my fears materialized. Nobody thought it was unprofessional. We were not forgotten. In fact, at the time, because it was so unusual, we got much more press for not working than we ever got from working.

H: Great. So I’m going to end by asking you for some inspirational words because you hate inspirational quotes. So do you have any words of inspiration for others in this field? Because, like I said earlier, pessimism reigns right now, and I’d love for someone who sort of looked at the sweep of history, and understood that actually things are getting better in a long-term view. Any thoughts on that?

SS: Well, I would rather be alive than dead. I would rather live in a democracy than in a dictatorship. I would rather be fed than hungry. I would rather be in peace than at war. I would rather be healthy than sick. These things actually can be measured, and there is very good numbers on these things. We have 200 years of really fantastic believable data, all of them are unbelievably better, and that is just good to remember. Make America Great Again only works when a lot of people think everything is shit, and it was much better in the past.

But if I ask a Republican, “So when was it great? 10 years ago?” It couldn’t have been, it was Obama. 20 years? 9/11. 50 years? Ronald Reagan ran with exactly the same line. It was never great in the same way that the world was never great — it’s an illusion. It’s some sort of, and there is also scientific evidence for that, there’s some sort of nostalgia in all of us that makes us forget the positive things in our past quicker than the negative things. So I think that’s a good thing to remember.