On October 5, 1842, a gruff Bavarian brewmaster named Josef Groll created the original Pilsner beer using ingredients from the Bohemian countryside: aromatic Saaz hops from the Žatec basin, golden malt from Moravia, and soft local waters. The one exotic introduction was the bottom-fermenting yeast that he carried with him when hired by the town fathers of Pilsen.

Article continues after advertisement

But unlike the wine regions of Burgundy, Barolo, Champagne, and Chianti, which took shape around the same time through innovative grape-growing and wine-making practices, Pilsner came to be considered not a geographical designation (appellation, in French), unique to its place of origin, but rather a style (Biertypus) or a quality designation (Beschaffenheitsangabe), reproducible anywhere. These different outcomes resulted in part from the physical nature of the products, since the brewer combined raw materials that shipped more easily and kept longer than the finished beer, while the vintner condensed bulky, perishable grapes into wines that could age for decades.

Moreover, the brewers of Pilsen lacked an established reputation and had to struggle for prestige against competitors across Central Europe and around the world. Ultimately, the meaning of Pilsner and other beer styles was a legal construct, determined as much by politicians and judges as by brewers and consumers.

Although named after particular towns such as Pilsen, Budweis, Munich, and Vienna, nineteenth-century beer styles arose from the heightened mobility of a globalizing era. Their development combined new British methods of malting and brewing with Bavarian advances in bottom fermentation. Beers accrued their reputations in continental and global markets, made possible by an extensive network of railroads and steamships.

And while brewers in Pilsen and elsewhere had once used relatively local ingredients, industrial production outstripped supplies, forcing them to purchase raw materials from international commodity markets. Finally, the expanding industry depended on the mobility of skilled workers, whether students traveling to learn new methods or brewmasters like Groll taking employment in other lands. As people, goods, and ideas moved back and forth at an accelerating pace, the desire to fix beers to particular locations was both understandable in theory and unachievable in practice.

Through stylistic conformity, imagined geographies, and commercialized consumption, beer became a modern commodity in the nineteenth century.

The nineteenth-century industrialization of lager brewing and the standardization of beer styles also resulted from advances in science and technology. Already in the late eighteenth century, large-scale British brewers had adopted thermometers and saccharometers to avoid costly failures, and those instruments were taken up by progressive brewers on the continent and in the Americas. The microscope was a particularly transformative tool, enabling scientists to uncover the mysteries of fermentation.

Major breweries established their own laboratories, and brewing scientists were among the leading theoretical chemists of the nineteenth century. They disseminated this knowledge and institutionalized their profession through brewing schools, research stations, and scientific publications, thereby creating international networks of knowledge. The application of analytical chemistry to industrial quality control, in turn, imposed quantitative standards that helped to ensure more uniform products while also restricting the creativity of practicing brewers.

The increasing mobility of consumers likewise contributed to changing tastes for beer. Industrialization brought migrants from the countryside to the city and from Europe to the Americas. Rising incomes from factory wages in the second half of the nineteenth century allowed workers to eat foods that had once been restricted to elites. The food-processing industry, with its new technologies of preserving and packaging, also held out the possibility of purity and freshness.

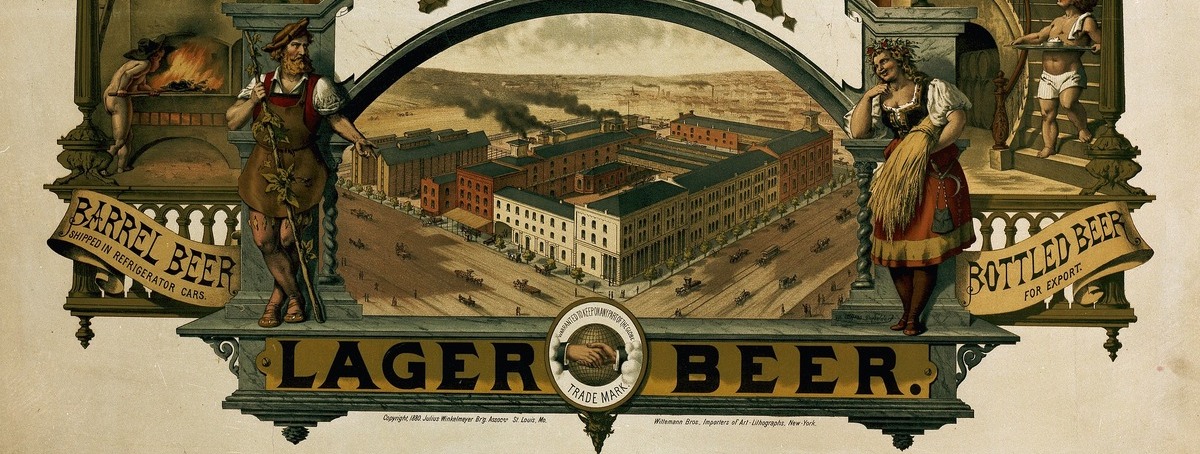

But as a result, consumers could no longer use their senses to judge quality in the marketplace and instead had to trust brand names. Nevertheless, advertising claims would only go so far if brewers could not ensure consistency from one bottle to the next. Brewers also created new spaces for consumption, transforming traditional taverns into elaborate beer palaces and gardens. Through stylistic conformity, imagined geographies, and commercialized consumption, beer became a modern commodity in the nineteenth century.

*

The two elegantly dressed young journeymen appeared respectable as they made the rounds of Edinburgh breweries in the fall of 1834, with their lacquered walking sticks and letters of recommendation from distinguished Scottish scientist David Booth. The stocky, blond, Munich brewer, Gabriel Sedlmayr, Jr., and his lanky, dark-haired, Viennese colleague, Anton Dreher, toured the factories with great interest, asking questions and freely sharing their knowledge of Bavarian lager yeast, which was unknown in Britain at the time.

As they visited the fermentation room at each brewery, one of the pair distracted their hosts, while the other plunged his walking stick into a bubbling vat of beer. A hidden valve opened to fill the hollow tube with brewing liquor, then closed again as it was withdrawn. Back in their lodging, the Germanic brewers analyzed the stolen samples with a saccharometer that Booth had taught them to use. “It always surprises me that we can get away with these thefts without being beaten up,” Sedlmayr wrote to his father. After returning home to the family brewery, Spaten, he applied his illicitly gained knowledge to craft a distinctive Bavarian lager. This novel beer, in turn, was copied by rivals across Central Europe.

In 1867, an Austrian industrial inspector named J. John described the popular altbayerische Art (old Bavarian style) as a “brown beer with seemingly stronger concentration brewed from dark malt and with an unusually long cooking of the hopped wort.” Although often attributed to sixteenth-century brewing regulations, crucial elements of the style were scarcely thirty years old at the time. Bavarian lager had not been, as a rule, dunkel, the dark-brown color that John and others had come to expect.

In 1829, as the young Sedlmayr set out on his journeyman tour of Central Europe and the British Isles, the Wochentlicher Anzeiger fur Biertrinker (Weekly Beer Drinker’s Gazette) reported a sample of Munich beers comprising twenty-eight weingelb (wine yellow, perhaps wheat beers), twenty-two hellbraun (light brown), and only one dunkelbraun (dark brown). Consistency of color as a marker of style had only recently been pioneered by the makers of London porter, and Sedlmayr helped to introduce this important, although often overlooked, British innovation to continental Europe.

As Sedlmayr sought to synthesize his newly gained brewing knowledge, he began by experimenting with novel malting techniques. In 1835, he brewed a Bavarian lager using English pale ale malt, which he dubbed Marzenbier (March beer). The amber color recalled the strong beers that were stored on ice for consumption through the summer and into early fall, especially at Oktoberfest, a recently invented tradition celebrating the marriage of Bavarian Prince Ludwig and Princess Therese in 1810.

For his signature “Munich” beer, Sedlmayr set a more ambitious and technically challenging goal, to brew a full-bodied, dark beer without the British trick of adding caramel sugar, which was forbidden in Bavaria. By replacing cantankerous, smoky ovens with the indirect and carefully regulated heat of British fluekilns, it became possible to toast the malt for about a day “at a gentle, clean heat, without being browned in the slightest degree,” and at the very end to “suddenly raise the temperature, which brings out the semi-caramelized substance, believed to explain the peculiar richness and aroma of the beer.”

Over the next four decades, Sedlmayr channeled his youthful masculinity—risking violence to steal beer—into building Munich’s foremost brewery. In Britain, he had declared, “all is new and entirely different from our ways,” and he sought to incorporate industrial methods throughout the brewing process. When Gabriel Jr. and his brother Josef inherited the business from their father in 1839, they brewed just over 24,000 hectoliters of beer. Sibling rivalry quickly divided the firm, and Josef built a successful brand called Leistbrau from their father’s original brewery.

Meanwhile, Gabriel Jr. renovated Spaten, excavating a new lager cellar in 1842 and installing a steam engine four years later. By 1851, with a production of about 43,000 hectoliters, he had outgrown the old space and began constructing a new factory with dedicated steam engines for each of three brewing houses. The company’s expanding export business also benefited from a bottling facility, a novelty in Bavaria, where tavernkeepers still held considerable political power and feared competition from bottled beers. By the early 1870s, Spaten’s 200 workers brewed almost 300,000 hectoliters of beer annually.

Although justly renowned for modernizing the Bavarian brewing industry, Sedlmayr was not a solitary pioneer. His father Gabriel Sr. had inspired and facilitated his research by establishing a brewing laboratory and purchasing a modern English malt kiln. Like his son, he had a transnational vision, importing hops from Bohemia, Flanders, and even the United States, and exporting beer as far as England.

Along with Georg Brey, who purchased the Lowenbrau brewery in 1818, the elder Sedlmayr experimented with Doppelbier and other varieties that had formerly been restricted to the aristocracy and religious cloisters. Brey also expanded ambitiously, competing with Sedlmayr to run the premier Munich brewery. Meanwhile, in 1829, Anton and Therese Wagner began renovating a former Augustinian monastic brewery, and after Anton passed away in 1845, Therese managed the business, installing steam engines and other innovations, until her death three years later. Outside Munich, brewers in Nuremberg, Kulmbach, Erlangen, Augsburg, and other towns likewise built export breweries.

Bavarian dark lagers achieved widespread popularity across Germany in the 1840s and 1850s. In Munich, beer provided a primary source of nutrition for many in the working classes. Single men, no longer bound to a master’s household, took their meals in taverns, where they consumed the beverage. Housewives meanwhile lined up with tankards outside of breweries to take home the daily beer to their families. Absorbing as much as half the daily wage, beer largely determined workers’ standard of living. When beer prices increased in 1844 and again in 1848, crowds broke into the homes of prominent brewers, tossing the Pschorr family’s grand piano out into the street, but scrupulously respecting the brewing equipment.

Elsewhere in Germany, Munich beer became gentrified, as brewmaster Ernst Ruffer later recalled sardonically. Taverns, “especially in little country towns, under the name of ‘Bavarian Beerhall,’ were cheerfully visited by a discriminating clientele, who preferred the ‘genuine Bavarian’ and so-beloved Doppelbier; many enjoyed it simply because it belonged to ‘high society.’” But fashion was not the only appeal. Like many industrial foods of the nineteenth century, lager beer was widely considered to have a fresher taste and more hygienic character than topfermented ales, which often tasted sour and were believed to harbor cholera. Especially in the 1840s, as the potato blight raged in Ireland and spread across northern Europe, a stomach-filling, double-strength beer offered a satisfying marker of wealth and status.

The growing demand for Bavarian beer offered enormous potential profits for brewers but also inspired new competitors. Even before Munich was connected to the German railroad system in 1840, the industrial city of Leipzig imported 10,000 hectoliters of Bavarian beer annually. By the early 1860s, special beer trains departed twice weekly from Munich for the Rhineland and Paris. To meet the demand for lager, Munich brewers had to purchase ice harvested from the Birnhorn glacier in nearby Austria. In Zurich, the arrival of the first beer train from Munich became enshrined in the historical memory of local brewers, who recalled “from that moment on, the beers of all Swiss breweries increased significantly in body, and the quality became much better.”

Competition not only raised standards, but also drove brewers to learn the new process. Leipzig cloth merchant Maximilian Speck von Sternburg traveled to Munich in 1836 to obtain the latest lager brewing technology, including plans for the Wagners’ reconstructed Augustiner Brewery. Meanwhile in Berlin, Bavarian migrants such as Georg Hopf and Joseph Pfeffer equipped factories with lager storage. Across Germany, as brewmaster Ruffer noted, the fashion for lager “forced brewery owners to abandon top fermentation and make dark, bottom-fermented beers with the same [Bavarian] taste and characteristics.”

The replicability of the lager recipe posed a dilemma for Sedlmayr and other exporters, although the genuine Bavarian article retained a special appeal. By 1870, the southern kingdom produced more than 10 million hectoliters of beer, one-third of Germany’s entire output—and not just because the people of Munich drank five times the national average. Secretive guild practices gave way to an open exchange of scientific knowledge, and the “industrial espionage” of Sedlmayr’s British mission or, indeed, the contemporary travels of Speck von Sternburg acquired the more neutral term “technology transfer.”

Perhaps ashamed by the betrayal of his Scottish mentor, Sedlmayr supported aspiring lager brewers throughout his long career. Even his singular triumph of associating the full-bodied, bottom-fermented, Bavarian lager with a distinctive dark color left a mixed legacy. Fashion was fickle, as London’s porter brewers had unhappily discovered.

Few visitors in the early nineteenth century might have guessed that the market town of Pilsen, on the road from Prague to Bavaria, would become world renowned for its clear, sparkling beers. Having grown rich from the business of anthracite mining, residents imported Bavarian lagers. In 1840, the town fathers decided to invest some of their mining profits in the construction of a municipal brewery. The first tasting, held on St. Martin’s Day, November 11, 1842, brought their home-grown beverage local acclaim.

But apart from the basic recipe of Saaz hops, Moravian malt, soft water, and lager yeast, little is known about how Pilsner acquired its legendary status. It was prized, at first, as an exotic “Bavarian” beer, and the malting process relied on British advances in indirect heating, like Sedlmayr’s Munich malt, but without the final burst of caramelization. The brewery’s capacity of just thirty-six hectoliters, about twenty barrels, meant that the beer was sold primarily in local markets. Brewmaster Groll, a difficult man by all accounts, was sent home when his contract expired.

Pilsner spread slowly in its first decades, through imitation as much as export. According to legend, a teamster named Martin Salzmann first introduced Pilsner beer to Prague about 1845, but rather than expand his carriage trade and profit from growing sales, he settled down in the Bohemian capital and opened a tavern. Although Pilsen’s burghers constructed a second brewhouse with larger kettle and mash tun in 1852, it took almost another decade for production to reach 40,000 hectoliters. Sales expanded more rapidly after 1862, with the opening of the Bohemian Western Railroad and the construction of a third brewhouse, followed twelve years later by a fourth.

In 1868, a writer for the Bayerische Bierbrauer (Bavarian Brewer) attributed the growing popularity of Bohemian beers to their “lightness, carbonation, mild taste and clear golden color.” The Pilsner brewery was only one of several regional exporters producing such a beer; others included Egerer and the Prague-based Kreuzherrenbier, Konigssaaler, Nussler, and Bubner. Curiously, Budweiser did not make the list; although already renowned for its beers, the town had only adopted bottom fermentation in 1852. The citizens of Pilsen could not even claim exclusive title to their town’s name after 1869, when a brewing corporation called Gambrinus opened nearby and started producing a similar clear beer. Thus, the golden Pilsner, like Sedlmayr’s dark beers, attracted imitators.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Anton Dreher’s Vienna brewery, Klein Schwechat, outshone the reputation of Pilsner. Like his traveling companion, Sedlmayr, he had experimented with combining English pale ale malts and Bavarian lager yeast in the 1830s. Whereas the Munich brewer used the recipe only to produce a seasonal specialty, Marzenbier, Dreher made the amber brew his signature Vienna lager. It became all the rage in the Austrian capital, and Klein Schwechat workers struggled to meet the demand from the rapidly growing population.

From an initial output of 16,000 hectoliters in 1836, production rose above 50,000 hectoliters by 1848, then tripled again in the following decade, making “Little Schwechat” the largest brewery in continental Europe at the time. The hyperactive Dreher opened two new breweries to capture regional markets: Michelob in the Saaz district of Bohemia, in 1861, and Steinbruch in the Hungarian capital of Budapest, in 1862, before his death the following year.

The example of Vienna lager illustrates the ongoing refinement of beer styles through an interaction between producers and consumers, ingredients and technology. Frankfurt brewmaster Friedrich Henrich recalled working as a journeyman for Dreher in 1858: “At the time he was famous as a maker of Marzenbier”—as Vienna lager was known in Germany—“and it was his wish that Marzenbier should be more full-bodied than it had been previously, and particularly that it should be different from highly attenuated lager beers.” Henrich’s listeners understood the reference to drier Bohemian varieties of beer, in which the sugars had been converted more fully to alcohol. The remark clearly indicates Dreher’s persistent concern with refining his brewing style—and with his competition.

Already by the 1860s, Central European brewers had created a spectrum of lager beer styles ranging from dark, full-bodied Munich to amber, malty Vienna and golden, dry Pilsner—and that was no accident. Even before the railroads had fully integrated European beer markets, brewers kept a close watch on their rivals and worked to ensure that their own products stood out for consumers. German-speaking migrants carried over this international competition to the Americas as they opened a new world of lager beer.

*

Although Bavarian migrants such as Valentin Blatz and Christian Moerlein were among the early German brewers in the United States, the knowledge of bottom fermentation traveled through many channels. The Pabst Brewing Company’s founder, Philip Best, acquired his original lager yeast from a Milwaukee neighbor who had ordered it from Bavaria. A delay in transit caused the brewer to fear the yeast would not survive, so he sold it sight unseen to Best for the cost of shipping. When the box finally arrived, packed with sawdust and wrapped in hop sacking, Best ran the yeast through a sieve to filter out debris.

As brewmaster Max Fueger later recalled: “Neither Philip nor I slept very much while we were trying the new yeast, but it was a success, although we made better lager beer after six months than we did the first time.” Through experiments such as this one, immigrants developed original styles of lager beer on the lakeshores of Milwaukee and far beyond.

German immigrants made Chile and the United States the pioneer lager brewers of the Americas, although, unlike elsewhere in the hemisphere, the indigenous peoples of these territories had limited alcoholic beverages of their own. Whereas Spaniards encountered native brewers of pulque and chicha in Mexico and Peru, English and Dutch founded the first breweries in their North American colonies. Even then, most settlers drank rum, gin, whisky, or hard cider.

By 1810 only about 150 breweries operated in the United States for a population of 7 million. In the southern states, enslaved and free women of color adapted African brewing traditions to New World ingredients, selling beers made of molasses and sarsaparilla root. Spanish settlers in Chile and California founded vineyards to satisfy their needs for sacramental wine and daily consumption. Chileans also made a version of apple cider called chicha, using the same term as the indigenous fermented corn beverage. British ale became fashionable during the wars of independence in the 1810s, and the inaugural banquet for President Manuel Bulnes in 1841 served Burton ale alongside Bordeaux wine.

German-speaking migrants carried over this international competition to the Americas as they opened a new world of lager beer.

Lager beer arrived in the Americas in the 1840s along with German migrants fleeing economic change and political unrest. Early arrivals were often farmers and artisans from Bavaria, Baden, and Wurttemberg, followed by political refugees from the failed liberal revolutions of 1848. Most settled with their families in the Midwest’s so-called German triangle between Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and St. Louis. Much smaller numbers, about 80,000, moved to Chile with official encouragement, founding colonies at Valdivia and Llanquihue, on the indigenous Araucanian frontier.

By the 1880s, proletarian migrants from northeastern Germany had largely replaced the earlier agrarian arrivals from the southwest, and the newcomers usually searched for industrial work in cities such as New York and Chicago. Nearly 5 million Germans came to the United States in the century after 1820.

Finding relatively cheap food and high wages, migrants generally improved their standards of living in the Americas, although they were not always welcomed at first. Chicago’s Lager Beer riot of 1855 resulted not from a shortage of beer but rather from Nativist attempts to ban the beverage enjoyed by the newcomers. German service in the Union Army during the Civil War created a positive view of the immigrants among northerners, many of whom learned to drink beer while serving alongside German units. Beer gardens became a conspicuous center of German American social life. Likewise in South America, settlers gathered in social clubs to eat, drink, sing, and play sports, and Chileans soon acquired a taste for “German chicha.”

Some notable early brewers, including Valentin Blatz and Christian Moerlein, brought a knowledge of bottom fermentation with them from Bavaria, while many others learned through practice in America, as did Philip Best and Max Fueger. A trade history published by John E. Siebel in 1903, One Hundred Years of Brewing, offered a sample of more than 500 profiles of brewers in the United States. Although the book is top heavy, favoring owners over workers, it suggests that prior experience was not a requirement.

Of the eighty or so brewers listed as arriving from Germany in the formative decade before 1850, only twenty made lager, and fewer than half of those came from Bavaria. These profiles also show that American apprenticeships were common, even among migrants who had learned the trade in their home country. Historian Perry Duis observed that newcomers usually landed in big cities like New York, Philadelphia, or Cincinnati, where they worked at established firms before setting out for smaller towns or the frontier to become their own bosses. Bavarian connections were likewise useful but not essential in Chile. The most prominent early brewer, a Prussian pharmacist named Carl Andwanter, founded the German settlement in Valdivia after the 1848 revolution and sent two of his sons, Richard and German, to study in Bavaria. Of the leading brewery owners in Santiago and Valparaiso in the 1850s, five were German, two Italian, and one Swiss.

Cheap grain and expensive labor shaped a unique approach to brewing in the Americas. Early lager brewers dug cellars from the waterfront bluffs in Milwaukee and St. Louis or in the hills around Cincinnati, but the costs of excavation encouraged a shift to icehouses by the 1860s. Natural ice was expensive, bulky, and messy, limiting the growth of breweries. The arrival of reliable refrigeration in the 1880s allowed for the construction of massive factory complexes with specialized buildings for fermentation, storage, and bottling.

Also in the 1880s, brewers began adding so-called adjunct grains, especially corn and rice, to the traditional Bavarian barley-malt recipe. Anton Schwarz, a brewing scientist who had trained in Prague before moving to New York, demonstrated the value of this technique for making bright, clear, and stable Bohemian-style beers. In Chile, the lack of a diversified industrial base limited brewers to machinery imported from Germany. Local farmers raised high-quality barley; hops also grew well, but the cost of labor made it prohibitively expensive to harvest them.

International migration also encouraged eclectic and innovative brewing styles. Dark Bavarian beers held sway until Americans discovered Pilsner beer at the Vienna World’s Fair in 1873. Within two years, “’Pilsner Beer’mania” had reached Cincinnati, and local brewers were creating their own versions following Schwarz’s guidance. To avoid false advertising, they listed the origins of the beer using phrases like “Schlitz (Pilsner) Milwaukie Beer.” By 1880, the golden lager had become so popular that Pabst’s Chicago sales manager wrote to Milwaukee pleading: “Can’t you give us a paler, purer beer?”

Meanwhile, after a visit to the town of Budweis, Adolphus Busch recreated a version of the Bohemian beer for a friend, Carl Conrad, to bottle and sell. The beer gained wide acclaim, and a rival soon copied it, right down to the label. When Conrad filed suit in 1880, the defendant replied that a town’s name could not be trademarked, and in any event, the beer was not actually made in Budweis. Conrad won the case by arguing that the beer’s name referred not to the town but to the Budweis method, although the recipe had in fact been concocted by Busch’s brewmaster. Busch later bought the rights and began distributing Budweiser through his own agents. Chilean brewers likewise produced a mix of Pilsner- and Bavarian-style beers, along with a less common Erlanger beer, named after a town near Nuremberg. It is not clear whether this style became popular through visits to the homeland, like Budweiser in North America, as a result of a single migrant from Erlangen who was copied by other Chilean brewers, or perhaps even from a chain migration of Erlanger brewers.

The industrialization of brewing took off in American societies almost simultaneously with the growth of lager beer in Central Europe. Although modeled on beers from the homeland, American brewers adapted their methods to the conditions and tastes of their new countries. Indeed, scientific advances that drove industrialization resulted from knowledge networks that spanned the globe.

__________________________________

From Hopped Up: How Travel, Trade, and Taste Made Beer a Global Commodity by Jeffrey M. Pilcher. Copyright © 2024 by Jeffrey M. Pilcher and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.