LINZ, Austria — The Russian artist and activist-in-exile Nadya Tolokonnikova is most famous for the 2012 performance “Punk Prayer” in Christ the Savior Cathedral in Moscow. It shocked Russian pieties and sent her and fellow Pussy Riot member Maria Alyokhina to prison for “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred.” In the West, where artists are not generally thrown in jail for their art, Tolokonnikova has been swathed in a kind of glamour that misses the point of the very real risk she continues to take to resist Putin’s authoritarian regime. Tolokonnikova merges her sex appeal with religious iconography in a way that is deeply disturbing to Russian sensibilities. It’s worth thinking about why radical feminist art can pose such a danger to political power, and what these artistic strategies can achieve — particularly now, in increasingly unpredictable times.

RAGE at OK Linz is Tolokonnikova’s first solo museum show to date. In paintings and engraved wooden reliefs containing text written largely in medieval Cyrillic vyaz calligraphy, the stark chromatic language of red and black speaks directly to violent political repression. Through their repetitive, prayer-like invocations, they draw on the psychological ordeal of the artist’s two-year incarceration and the defiance required to reclaim her artistic agency. One of the rooms features a reconstruction of her bleak prison cell with original letters and photographs; on the opposite wall, video screens play clips of the celebrated feminist collective’s performances and actions.

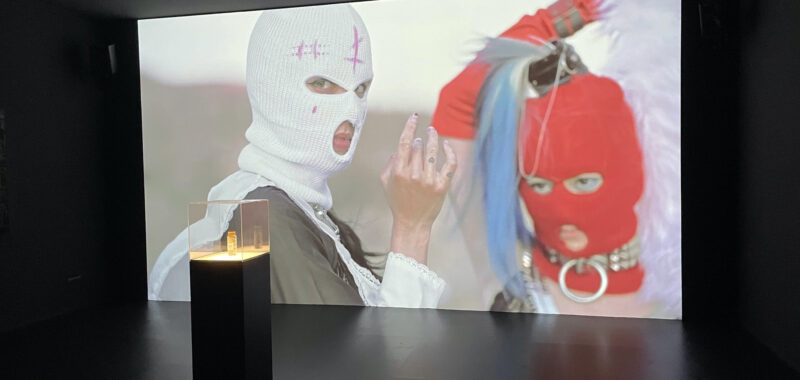

In a darkened room called the “Rage Chapel,” stylized portraits of Pussy Riot members line the walls like masked icons, with messages of rebellion hovering halo-like above their heads. “Fear is coming up again help me to chase it away” is an appeal from Tolokonnikova’s song “Panic Attack,” testifying to the anxiety of a young woman locked up in harsh conditions and the strength she managed to mobilize.

Some of the words in Tolokonnikova’s paintings are taken from her closing statement in court prior to sentencing; the works also include lyrics to the song “Rage,” which she wrote following Alexey Navalny’s imprisonment. Her giant “Damocles Sword,” dedicated to the political opposition figure, is a four-meter-tall (∼13-foot) knife blade that hangs over visitors’ heads, calling to mind the precarious situation of artists and activists in Russia and abroad living in constant danger of targeted persecution. An adjacent room features documentation from the protest piece “Murderers,” performed in Berlin by a group of balaclava-masked Pussy Riot members in outrage at Navalny’s death.

Tolokonnikova’s video “Putin’s Ashes” (2022) depicts the ceremonial burning of a large portrait of Vladimir Putin. It’s part of an installation titled “Putin’s Mausoleum,” in which small vials containing the ashes are displayed like relics; on the walls are wooden reliefs depicting the artist’s vulva and other images, collectively titled Dark Matter. Like the Pussy Riot Sex Dolls series — used sex toys in platform combat boots reconfigured as symbols of female empowerment and resistance — the pieces embody an aggressive feminist strategy aimed at ridiculing male power and patriarchal structures everywhere, and they led to her renewed arrest in Russia, this time in absentia. In light of the recent act of vandalism against the Austrian exhibition, the message that emerges is not merely the force of resistance and resilience, but the danger of retribution.

RAGE breaks with the Western fetishization of Tolokonnikova’s celebrity to bring together major bodies of work in which the artist interrogates her identity, all that she has risked and sacrificed, and the price she has paid for her artistic and intellectual integrity. After admiring bravery from afar, one day, perhaps sooner than we think, those of us in relatively stable Western nations may have to fight for the freedoms we’ve long taken for granted. Maybe it’s time to ask ourselves to what degree we — like the artist or, for that matter, the university students who sacrificed part of their education to protest the massacre in Gaza throughout 2024 — are willing to put our own lives on the line to speak up against oppression and injustice.

RAGE continues at OK Linz (OK-Platz 1, Linz, Austria) through January 6. The exhibition was curated by Michaela Seiser and Julia Staudach.