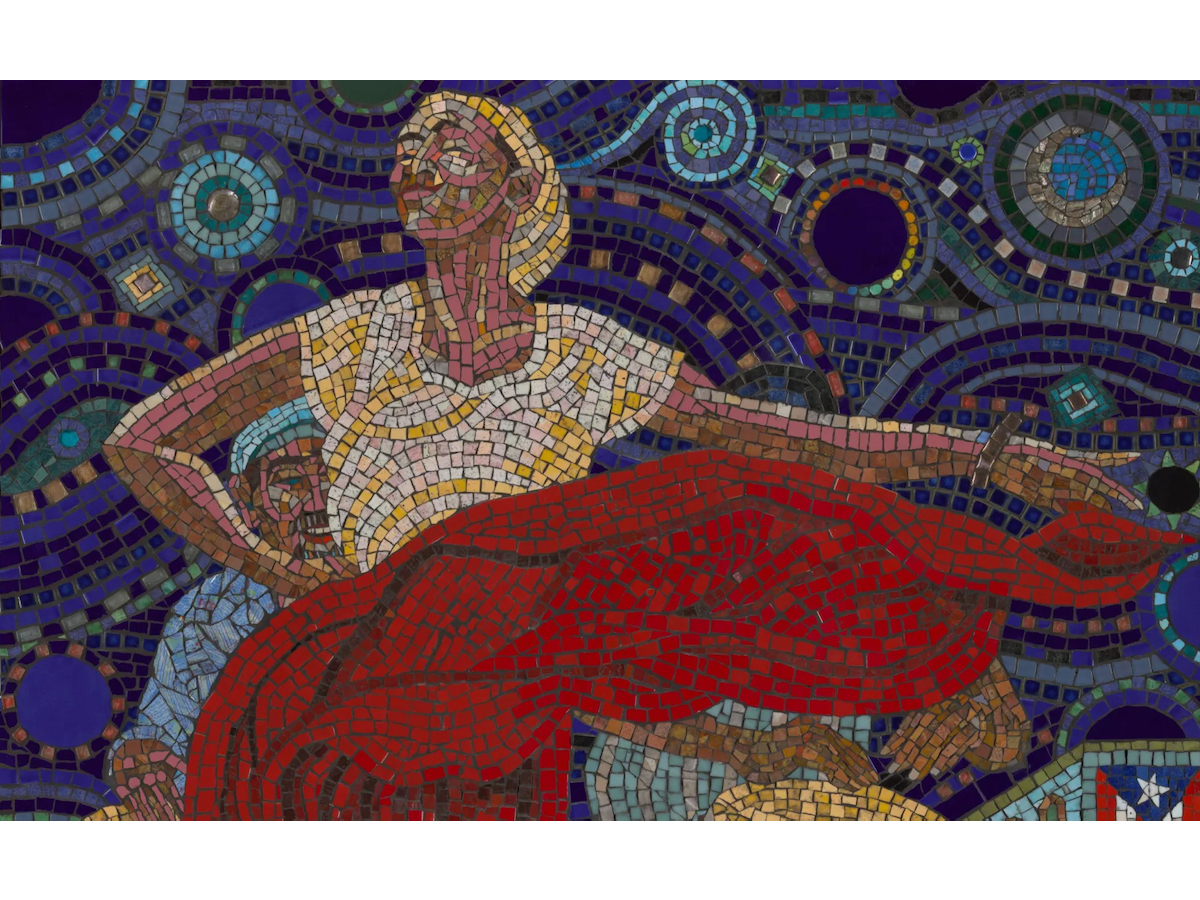

To me, one of the most distinct demarcations of New York City’s El Barrio — Spanish for “the neighborhood” — are the glistening mosaics adorning building facades and subway station walls. Depicting drummers and jazz singers and often hinting at religious references, these accessible yet gripping images imbue the neighborhood I grew up in with color, rhythm, and complexity. But it wasn’t until I went to the Museum of the City of New York’s centennial exhibition, Byzantine Bembé, that I learned about the profound cultural and social dynamics that underpin these public works. Painter, illustrator, and printmaker Manny Vega — now the museum’s first artist-in-residence — created many of these mosaics and murals in celebration of important figures in Puerto Rican and Latinx communities, telling the stories of his very own “El Barrio” through his work.

Hanging above the entrance of the exhibition, a beaded Gelede mask, worn by male Yoruba dancers to honor maternal figures, signals the central themes in Vega’s work. His own mother and sister, whom he refers to as “the feminine divine,” are often depicted among local social justice figures, musicians, and religious figures who shaped his upbringing as well as his community, such as Puerto Rican educator and civil rights activist Dr. Antonia Pantoja, Cuban master percussionist Chano Pozo, and his high school art teacher Marshall Davis. The Yoruba beading technique — also prevalent in his costume design — points to the prevalence of pan-African spiritual practices in the diaspora to this day.

Throughout the exhibition, a mélange of pen and ink sketches, Sharpie drawings, etchings, watercolors, and mosaics convey Vega’s multidimensional visual lexicon, which he calls “Byzantine hip-hop.” For instance, a textured and multisensorial 2009 mosaic of jazz pioneer Tito Puente feels as vibrant as the jazz-centric music that plays throughout the exhibition.

Another striking etching, “San Lázaro en El Barrio” (2019), depicts Saint Lazarus coming back from the dead while Saint Michael strikes evil spirits in front of the tenements on 110th Street and Fifth Avenue. It conveys Vega’s profound connection to Candomblé, a 19th-century Afro-Brazilian religion developed by enslaved people that lives on in El Barrio. Inspired by a photograph by Hiram Maristany, another etching plate features the body of Young Lords activist Julio Roldán, who died in 1970 while incarcerated at a downtown prison referred to as “the Tombs,” raising questions around racial politics and criminal justice in New York.

The piece that might best encapsulate the ethos of the exhibition is a 2023 mosaic entitled “WTF.” Beneath its depiction of a couple on a motorcycle are the words “WTF 2020,” with little other imagery. To me, the wording specifically recollects the chaos of the pandemic, demonstrations, and social movements that defined the year. It embodies the way that Vega’s mosaics continue to celebrate the rich cultural tapestry of El Barrio and the spirit of its residents, inviting visitors to reflect upon the heritage, identity, and activism of our neighborhoods.

Byzantine Bembé: New York by Manny Vega continues at the Museum of the City of New York (1220 Fifth Avenue at 103rd Street, East Harlem, Manhattan) through December 8.