It’s been a rough year for the literary festival.

Sparked by a campaign from Fossil Free Books (FFB), nine festivals that previously relied on support from the Baillie Gifford Foundation dropped or lost that company’s sponsorship after the firm failed to divest from fossil fuel companies and interests allied with Israel’s military.

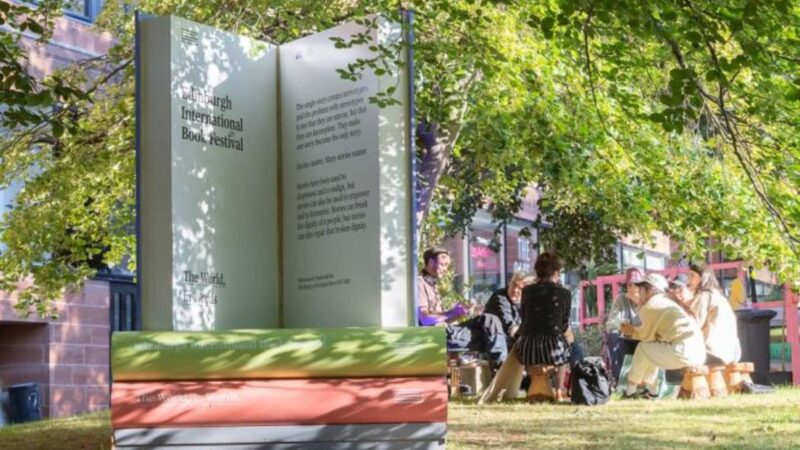

As my colleague Dan Sheehan has reported, the Hay Festival was a crucial first domino—but BG cancelled its remaining sponsorships in light or expectation of additional protests. In the UK, the Edinburgh international festival, the Wimbledon BookFest, and the Borders book festival were affected, among other celebrations.

And as we’ve seen stateside with the unfolding crises at PEN America—who cancelled their World Voices Festival earlier this spring in the face of similar criticism—public opinion has moved the needle. As Naomi Klein wrote in May in conjunction with Fossil Free Books’ statement, “Literary festivals rely on the labour of writers, editors and translators. We donate our labour because we love to gather and meet our readers, but we have the right to demand that these gatherings divest from the forces causing death and destruction on an unfathomable scale.”

While it’s disappointing that calls for corporate divestment are still unmet, it’s slightly heartening to see culture workers exercise their modicum of power. Creatives all over the world stand against the genocide. And that momentum isn’t going away.

Last week in The National, Omar Hamilton called for literary festivals to take firmer stances on Gaza. And in Mondoweiss last week, the collective Publishers for Palestine called for a round condemnation of the Frankfurt Book Fair based on its alliance with Israel.

But if festivals are to survive this moment, they’ll need a new funding model. As Culture Unstained, an organization that aims to “end fossil fuel sponsorship of our culture,” told The Guardian, “Not only must [festivals] find funding in a difficult economic landscape, but they must also do so during a change in the sector’s “approach to ethical sponsorship.”

*

It’s worth thinking through what whole new models could look like. Though ethical sponsorship sounds peachy, as members of FFB have noted, corporate sponsorship of any kind may be terminally unsustainable given the ethical conflicts occasioned by the, um, free market.

Though on this side of the pond we can but dream of state-sponsored support, the organizing grounds for arts funding are better than they have been in a while. So that may be one path, in the long term.

Alternately, the money could come from inside the house. Sofia Akel, founder of the Free Books Festival, recently suggested that publishing houses should budget for festivals. Earlier this year, Bloomsbury attempted this very feat, via a large multi-festival donation meant to cover the gaps left by BG. Though a curious prospect, it’s a little hard to imagine this one at scale. A lot of ink has been spilled about the dire financial straits of the publishing houses, and limited bandwidth for publicity is a perpetual sticky wicket.

The locally sponsored festival may be a more solid bet. In the UK this June, the Bradford Literary Festival partnered with Network Rail to bring books to the people. And Edinburgh’s book festival continues to be sponsored in part by independent bookshops.

Absent high ticket prices, such partnerships may not wield enough to cover the full sticker price of a large festival. To pull of larger affairs, philanthropists may need to be courted. If we think ethical corporate sponsorship is possible, that is.

Ball’s in your court, MacKenzie?

Image via