Take a walk on Sixth Avenue in Manhattan and, as you pass through SoHo, there is an innocuous-looking warehouse on the west side of the street overlooking a small park and a statue of the Uruguayan national hero José Artigas. Set back from the avenue and dwarfed by its more imposing neighbor, the Forhan Building, you might not even notice it, but this building is one of the last remnants of a once-thriving global subculture that tried to change the world.

Article continues after advertisement

It is the current home of the Dahesh Museum of Art, an institution created to display the art collection of a miracle-working mystic known as Dr. Dahesh, who first appeared in Jerusalem in the late 1920s and could perform amazing feats that contradicted the established laws of nature. Dr. Dahesh, even his enemies agreed, was extremely charismatic and the stories that were told about him defied belief. He could make objects appear out of thin air, heal the sick, and even communicate with the spirits of the dead.

In the mid-twentieth century, long before his collection ended up in New York City, he traveled the Middle East, thrilling, baffling, and offending people in equal measure. In Palestine, he was accused of using his paranormal abilities to swindle a wealthy widow out of her fortune. A few years later, in Beirut, he began his own religious movement named Daheshism, which managed to attract a devoted circle of followers among the country’s educated elite and terrified some of Lebanon’s most powerful men.

Occultists promised that they were the midwives of a new modern age, one that would bring untold miracles.

Compelling though Dr. Dahesh’s story might be, he was just one small part in a much larger transnational movement that flourished in the years after the First World War. Let us call this movement “the occult”—a vague and slippery term but the best one there is. It included a series of philosophies from Theosophy and Spiritualism to Rosicrucianism and parapsychology and was populated by a huge cast of eccentric and charismatic gurus, prophets, and sages.

Insofar as a definition is possible, the occult (from the Latin for “hidden”) was a belief system that asserted that there is more to our existence than the perceptible, physical world. Other worlds exist, which the tools of conventional science or logic cannot fully understand but which exert a mystical power over everyone. It was a worldview based on wonder, on the possibility that marvelous things were truly possible. Of course, this also sounds uncomfortably like a broad description of religion, and any attempts to define the occult will naturally tread on the toes of several established religions.

If a good abstract definition of the occult is hard to find, perhaps a historical one will make things clearer. Almost every modern occult movement can, directly or indirectly, trace its roots back to a single, seemingly insignificant event in a farmhouse in upstate New York, around twenty miles from the shores of Lake Ontario. In Hydesville in 1848, two young sisters, Kate and Maggie Fox, heard disembodied knockings on the wall of their house. After some investigation, they discovered that these bangs emanated from the ghost of a man who had died in the house many years earlier, and soon they came up with a way to communicate with him. As the girls honed their skills, they found that they had the ability to communicate with a vast range of other departed souls in the spirit world too. What could have been a local ghost story, confined to the pages of obscure histories of upstate New York, quickly expanded much farther.

The story of the Fox sisters captured the world’s imagination, and by the early 1850s, they were international celebrities. Reports began to emerge that other people had managed to communicate with the spirits just like the Fox sisters, all across the United States and in places as far away as Havana, Paris, Rome, Vienna, Damascus, and London. One writer in America joked that death would no longer have to mean an end to your social life: installing “an electric telegraph across the Styx before they get one across the Atlantic would make death less of a separation from friends than a voyage to Europe.”

These astounding phenomena spawned an entire religio-philosophical movement. A significant number of people, disenchanted by the failures of traditional religions and enthused by the possibilities of modernity, were fascinated by the idea that a portal had been opened into the world of the dead. So many barriers were being broken down in the nineteenth century—social, scientific, economic—and, soon, the one between life and death was looking decidedly fragile too. A new creed of Spiritualism was born, and figures from Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Queen Victoria, from Charles Dickens to Abraham Lincoln and Napoleon III, were all said to have experimented with spirit communication. With no central organization or holy texts to speak of, it took only a few years for splinter groups to emerge, taking Spiritualism in strange new directions.

There was John Murray Spear, who, in 1853, received a series of instructions from some illustrious spirits (including Socrates and Benjamin Franklin) that gave him a detailed blueprint for the construction of a perfect society. Following their advice, he set up a model community in upstate New York called the Domain (or, sometimes, Harmonia). Surrounded by followers, he set to work on a variety of different projects, including, most notably, an ultimately doomed quest to build a perpetual motion machine. And there was Paschal Beverly Randolph, who immersed himself in the doctrines of occult brotherhoods in the Middle East and returned to America bringing the secrets of hashish and “sex-magic.”

The occult expanded and evolved throughout the nineteenth century, and by the beginning of the twentieth, its ranks were filled by a succession of enthusiastic followers. In the front lines came the artists and writers. The great poet W. B. Yeats and the novelist D. H. Lawrence both explored the Spiritualist-inspired, esoteric movement of Theosophy, which had been created by the eccentric Russian aristocrat Madame Blavatsky in 1870s New York. Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries, spent his final years as a passionate proselytizer for Spiritualism. Painters found their own inspiration in the new ways of seeing the world that the occult offered, from Wassily Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich to Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian.

However, these unusual belief systems did not attract only creative souls, who are typically allowed more license to dream than the rest of us. There were more conventionally minded adherents too—scientists and politicians. The British physicist Sir Oliver Lodge was famous for his early twentieth-century efforts to investigate paranormal phenomena, and he published widely on the subject. Tsar Nicholas II and his wife were devoted to the charismatic and controversial holy man Rasputin. Academics at Harvard, Yale, and the Sorbonne experimented with the paranormal. The University of London and Duke University both had their own dedicated parapsychology labs.

Read about almost any major personality of the early twentieth century and you will soon stumble upon some aspect of the occult—if not through them, then perhaps through their aunt, their cousin, or their brother. This spiritual movement reached its last great zenith in the aftermath of the First World War. Palm readers, clairvoyants, hypnotists, mind readers, jinn summoners, and Spiritualists were springing up everywhere. In 1926, one Spiritualist medium testified before Congress that she knew “for a fact that there had been spiritual séances held at the White House with President Coolidge and his family.” She also alleged that she knew of several senators who regularly used the services of mediums.

Across the planet, the 1920s were a time of crisis and of rebirth. A new world was forming on top of the wreckage of the past and almost anything felt possible. The occult’s belief in the existence of other worlds beyond our own was literal but it also had a metaphorical aspect. The material world was full of drudgery, suffering, and injustice; opening the door to a spiritual world could guide humanity to a brighter future. Occultists promised that they were the midwives of a new modern age, one that would bring untold miracles.

*

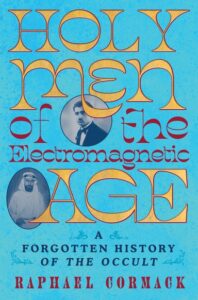

Telling the comprehensive story of something as vast and obscure as the occult is an impossible task. It is a deep and murky ocean of interconnected ideas, whose adherents plucked philosophies from different sources and stitched them together in their own idiosyncratic ways. Instead, this book will follow the lives of two men who rode this tide of wonders to play their own small but important part in the transnational tale of the early twentieth-century occult. Their stories are now largely forgotten, but they will guide us through the modern world and capture the hopes, anxieties, and neuroses of this troubled age. The miracle men of the 1920s and 1930s talk about hope and progress, but their stories were often tinged with that darkness, which hung heavily over so much of the twentieth century.

The first, Dr. Tahra Bey, born in Istanbul, traveled across Europe out of the ruins of the Eastern Mediterranean until he reached France as a refugee in 1925. In Paris, advertising himself as an “Egyptian fakir” from a long line of mystics, his ability to manipulate his physical body in inexplicable ways using the power of his mind made him a summer sensation. This stranger from the East could control his heart rate, pierce himself with sharp blades without feeling pain, and even shut his body down completely, entering a death-like state that could last hours or even days, then have himself buried alive before a stunned audience.

In the years after his awe-inspiring Parisian debut, he became a fixture of the European stages, and crowds lined up to see his strange marvels in the flesh. He had come to a Europe unmoored by the catastrophic events of the First World War and searching for answers in new places. Dressed in exotic Eastern robes and talking about a forgotten Eastern science of the spirit, Tahra Bey gave Europeans exactly what they wanted to hear. In doing so, he became not only famous but also very wealthy. His demonstrations were so popular that innumerable copycat “Egyptian fakirs” appeared across the Western world as fakir fever spread from Warsaw all the way to Los Angeles.

Many of these imitation fakirs adopted the Ottoman honorific Bey (a title similar to “Sir”) in emulation of Tahra Bey. There was a Rahman Bey, a Tatar Bey, and a Thawara Rey, who had obviously slightly misunderstood the significance of the word Bey. Some of them lasted only for a few months, but others stuck around for several decades. One of these many copycats, Hamid Bey, toured America in the late 1920s and early 1930s before establishing his own spiritual movement, from a house in the Hollywood Hills, known as the Coptic Fellowship of America, which survives to this day, long after its founder’s death.

The miracle men of the 1920s and 1930s talk about hope and progress, but their stories were often tinged with that darkness.

The second part of this book tells the parallel story of Dr. Dahesh and the Middle Eastern occult. At the same time that Tahra Bey was astounding the European public with his spiritual mastery over his body, Dr. Dahesh was spreading his own form of occult knowledge through the Arab world. From his first appearance in Jerusalem in 1929, Dr. Dahesh embraced the doctrine of Spiritualism and the science of hypnotism to become one of the most well-known proponents of an Arabic-speaking occult.

When he finally settled in Beirut to launch his eponymous religious movement, he had managed to shape a persona that was the unmistakable product of the twentieth-century Arab world. There were no appeals to the “mystical secrets of the East,” which did not hold the same allure here as they did in Paris or New York. Instead Middle Eastern occultists harnessed the powers of science and progress for their cause, guiding the region toward a new, modern, independent future.

The story of the occult in the 1920s is a truly global tale, and the spiritual movements of East and West interacted in unexpected ways. The action will pass through six continents, touring the cabarets of Montmartre and Cairo, walking the streets of golden-age Beirut, passing through yoga retreats in Los Angeles, seeing riots in Jerusalem and carnivals in Rio, before finally returning to Dr. Dahesh’s museum in Manhattan.

Along the way, we witness some of the most devastating events of the twentieth century: the fire of Smyrna, the Great Revolt in Palestine, the Nazi occupation of Paris, and the Lebanese Civil War. The narrative is based on historical material from across the world that was written in many different languages—among them Arabic, Armenian, Turkish, French, Greek, Portuguese, Italian, and English. The cast of characters includes stateless migrants, a Palestinian nationalist poet, an Anglo-American psychic scientist, a Lebanese artist, a Midwestern psychologist, and a celebrity Indian yogi.

The interwar period was the setting for a great showdown between rational and mystical worldviews—the clash that the historian James Webb called “one of the greatest battles fought in the twentieth century.” This book tells the history of this conflict from the perspective of the losing side. The occult was based on promises about the metaphysical world beyond the veil, where laws of nature and logic did not necessarily apply. In the fragile and ever-changing world of the early twentieth century, this made the esoteric a perfect breeding ground for grifters.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s a battalion of charlatans, fantasists, and swindlers, armed with little more than their charisma and some larger-than-life claims, managed to inspire cultlike devotion in their followers. Neither Tahra Bey nor Dr. Dahesh escaped accusations of fraud or quackery; both had serious run-ins with the authorities. Were they brave visionaries or unscrupulous con men? Did they have a noble dream or a dangerous fantasy? Devoted adepts vigorously defended their prophets, saying that everything new and unexplained always faced opposition at first. Skeptical members of the public were less sure and some were actively hostile: just because something was new did not mean it was good.

These battles between the occult and its doubters were the central battles of the 1920s and 1930s, decades when many were trying to cast aside the corrupted relics of the past to reach a brighter future. The logic of the nineteenth century had been discredited by the events of the twentieth. Tahra Bey and Dr. Dahesh were offering a new kind of logic for the new age, which would be built on different foundations. Like the Surrealists, who were their contemporaries, they revolted against bourgeois rationalism to create something different. Bizarre and unconventional as these holy men might have been, they were at the cutting edge of modern debates. The central question of the occult was also the central question of the twentieth century: Is another world possible?

__________________________________

From Holy Men of the Electromagnetic Age: A Forgotten History of the Occult by Raphael Cormack. Copyright © 2025. Available from W.W. Norton & Company.