SANTA FE — I’m standing in a low-lit gallery, looking into a floor-to-ceiling glass case displaying three textiles: one, a horizontal field of black and white parallelograms; another, a spread of vertical brown, red, and beige zigzagging lines that form a scalloped edge on either side; the third composed of wide horizontal bands of vertical zigzags, this time black and beige, along with narrower red bands punctuated by a series of diamond shapes outlined in black. The visual vibrations and patterns feel completely of the earth and the human hand. Each of these works — one tapestry and two blankets — appears timeless, but in fact they were created in two different centuries.

The works are part of Horizons: Weaving Between the Lines with Diné Textiles at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (MIAC). To organize the exhibition of over 30 textiles, photographs, and related items (e.g., dye samples, yarn swatches, digital media), co-curators Hadley Jensen and Rapheal Begay (Diné) collaborated with a Diné advisory committee; a similar approach was used for Grounded in Clay at the MIAC last year.

Making my way through the exhibition, I learned that what I saw as a scalloped edge is called a wedge weave, an uncommon style used for a short period in the 19th century, this one created as a blanket circa 1895 by a Diné artist once known. Fiber artist and weaver Kevin Aspaas, along with other advisory committee members, generously offers valuable insight like this printed on information panels. He incorporates the same style today in his own impressive weavings, some of which are on view in Horizons.

Elsewhere in the gallery, I was drawn to Tyrrell Tapaha’s expressive pictorial works, such as “Chaos at Four Kornerz” (2024) installed near a wearing blanket with spider design (1860–80), again by a Diné artist once known. I also spent time reading the visual stories woven into a pictorial blanket (c. 1885) placed at the exhibition’s entrance. The blanket’s scale, detail, and depiction of a train, figures, plants, animals, and geometric designs held my attention so intensely that I didn’t notice the digital tablet installed nearby that provides a recorded over-the-shoulder view as advisory committee members describe what they recognize in the piece.

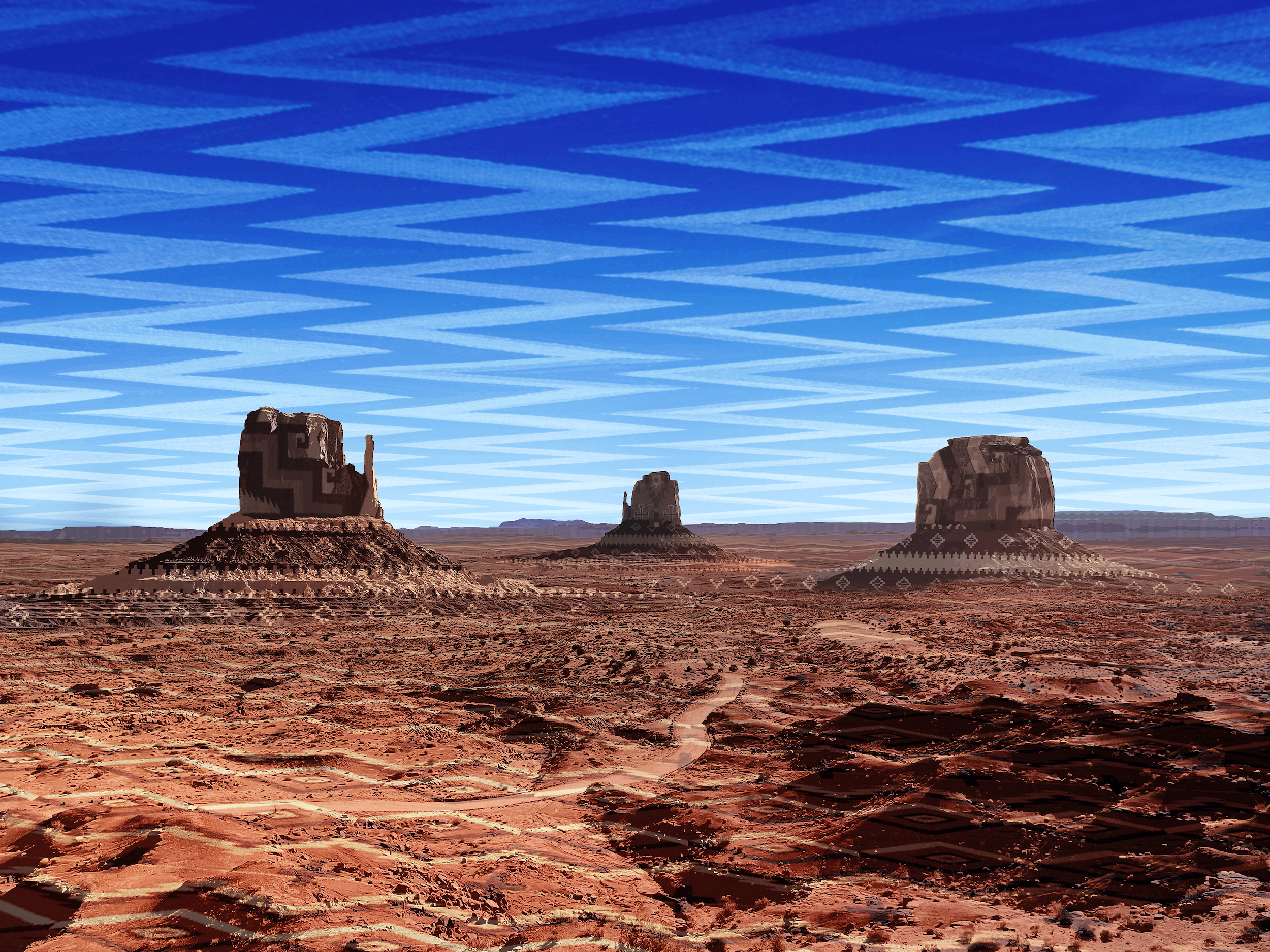

The blanket is suspended from the ceiling and hovers in front of a color photo mural, an enlargement of Begay’s “Navel (Hunter’s Point, Arizona)” (2017), portraying a house with sheep in a corral at the foot of a mountain. Begay’s photographs act as backdrops throughout the show, adding ambiance but detracting from their merits as artworks in their own right, which they are; Begay is a photographer based in Arizona. Similarly, through her digital collages depicting Southwest landscapes, Darby Raymond-Overstreet “aims to reclaim the visual language described by Diné weaving tradition.” The patterns overlaid on her images reflect those in several of the textiles on view. Had I encountered either of these artist’s photographs in an exhibition of their own, I could’ve imagined their connection to weaving because of the imagery itself. Seeing them in such close proximity to the textiles quickly flattened any curiosities I may have had.

On the one hand, the pairings and proximities in Horizons helped contextualize selected textiles, the makers’ experiences, and the show in general. On the other hand, the materials created the impression that viewers will not (or cannot) make connections between weavers and their stories, wool and sheep, weavings, and the land through the information offered by the works themselves — even if limited or culturally specific. Perhaps my impressions and biases point to inherent challenges in an exhibition of historical and contemporary works within an anthropological institution such as MIAC; the committee alludes to such in their description of the show as one that “strives to advance new interpretive frameworks that specifically work with, and towards, decolonial and community-oriented methodologies.” Horizons does indeed employ a model that leverages a collective perspective, but it made for a rather crowded viewing experience.

Horizons: Weaving Between the Lines with Diné Textiles continues at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (710 Camino Lejo, Santa Fe, New Mexico) through February 2, 2025. The exhibition was curated by Dr. Hadley Jensen and Rapheal Begay in collaboration with Lynda Teller Pete, Kevin Aspaas, Larissa Nez, Tyrrell Tapaha, and Darby Raymond-Overstreet.