CHICAGO — What’s art got to do with war? A lot, actually. It’s an effective arena in which to wage it, via intentional cultural destruction like that perpetrated by the Taliban when they blew up the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001, by the Nazis when they looted the collections of Jews during the Second World War, by the British when they sacked the City of Benin in 1897. More recent acts of this sort include the hundreds of Ukrainian heritage sites damaged by Russian missiles and dozens, perhaps hundreds, of places in Gaza destroyed by Israeli airstrikes.

During wartimes, violence befalls art. But art can be a counterattack too, a means by which a victimized populace fights back. In Women at War: 12 Ukrainian Artists, currently on view at the Chicago Cultural Center, opposition takes the form of experimental film, classic photojournalism, miniature landscape painting, even conceptual stone carving. The exhibition, first mounted by independent curator Monika Fabijanska in New York, presents artwork as a cry of rage, a way to fund the opposition effort, to share stories of grassroots resistance, and to register the most horrible of realities. Everything in Women at War has been made since 2014, when Russia seized Crimea; a few works postdate the full-scale invasion begun in 2022. The creators are four generations of women artists born in Ukraine, and many of them have become refugees over the past two years. Rarely has the wall labels’ brief biographical information — born here, lives there — so moved me. The exhibition’s one historical inclusion — a folksy, feminist sketch by Alla Horska that was the basis for a large outdoor mosaic on a building in Mariupol that has somehow survived bombardment — resounds with a harrowing matrilineal echo due to the artist’s death in 1970 at the hands of the KGB.

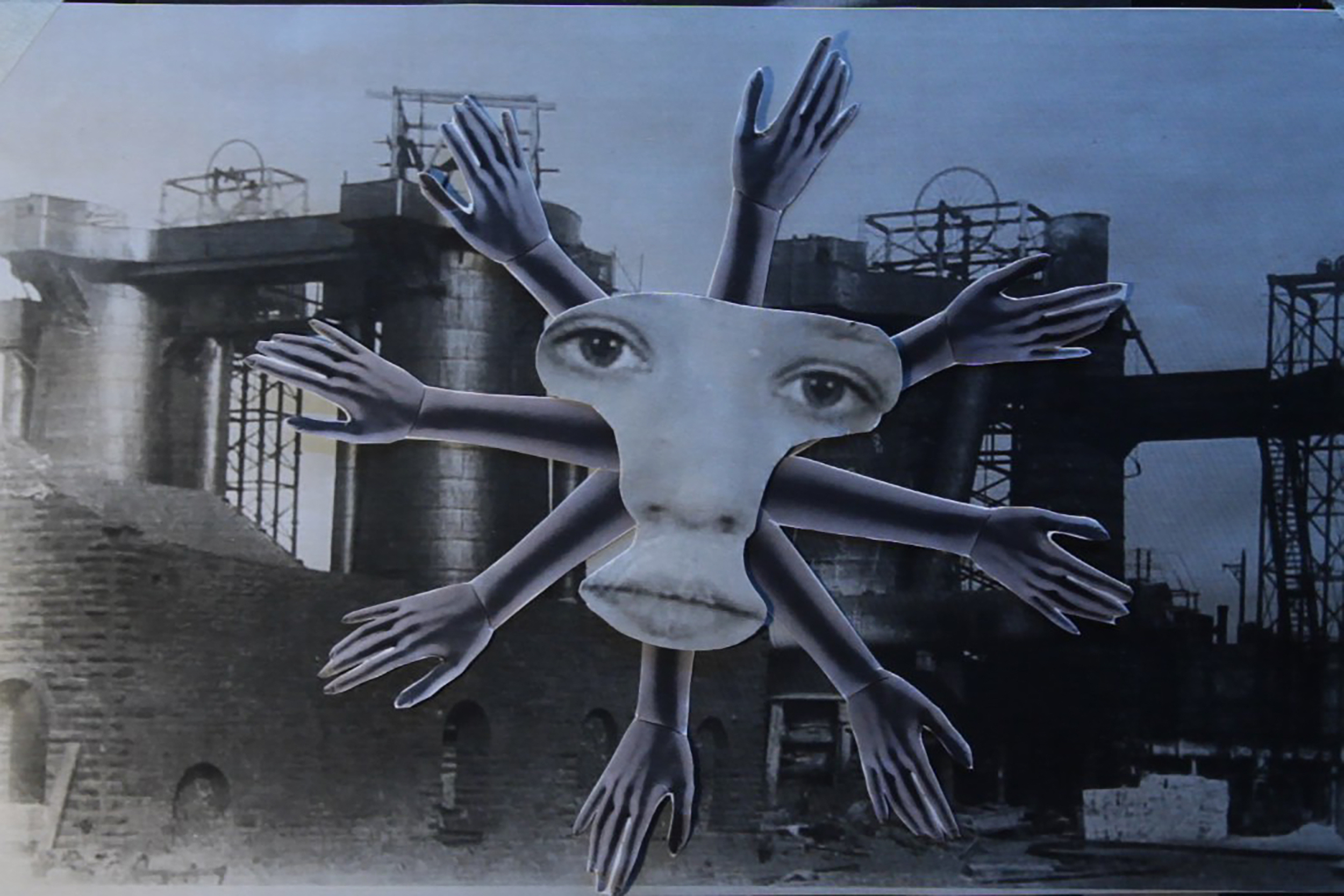

Much of the artwork in Women at War is very hard to look at. The most nightmarish are nine heavily marked ballpoint pen and watercolor pictures by Vlada Ralko, part of Lviv Diary, an ongoing series published daily on Instagram and currently numbering about 500. In them bodies are mutilated by missiles and sickles, terrifying beasts roam, death is everywhere. Nearly as brutal are Dana Kavelina’s spare pencil drawings of phallic war machines, huge soldiers, the women they raped, and the children born from those crimes. Traced on wrinkled, torn paper, the sketches are drained of color but for red lines marking the bloody ties that link their figures through violent copulation, enforced silence, and cruel paternity. Kavelina’s “Letter to a Turtledove,” a 20-minute video-poem, channels the sadistic surrealism of living in a war zone via a dizzying montage of cut-paper animation, handheld footage of recent fighting, suffocating body art performance, and archival footage of industrial Donbas run backwards, as if it could all be undone.

Beauty and charm are on view too, but deceptively. Three tiny watercolor landscapes by Anna Scherbyna, each just a few inches across, could not be lovelier. But close looking reveals that under blue skies and amid lush greenery stand ruined hospitals and a roofless airport, sights seen when the artist traveled through the Luhansk and Donetsk regions on a human rights monitoring mission. Whimsical illustrations by Alevtina Kakhidze tell the story of Strawberry Andreevna, a retiree living in Donbas and selling fruit and flowers at the local market. The style is quirky and naïve, yet the tale is not: the title character is the artist’s mother, given a nickname to protect her identity while she struggles to stay alive in a separatist-occupied territory. Individual panels narrate her daily trips to the cemetery outside of town, the only place with cell reception for calling her daughter; the checkpoints she must pass on her way to and from her garden plot; the cellar where she hides while a neighbor is killed; and finally her death, from cardiac arrest, while attempting to cross the demarcation line to collect her pension.

Uncanny artworks prevail as well. Zhanna Kadyrova presents what looks like a large round loaf of bread, partially sliced, but it is in fact a smooth river stone expertly cut by her partner, Denis Ruban. Many such rocks were harvested by the duo after their relocation to a remote village in the Carpathian Mountains to escape the bombardment of Kyiv. Titled “Palianytsia” after the Ukrainian bread famously mispronounced by Russians — a name given more recently to the country’s latest strategic weapon, a broad-winged cruise missile — all sale proceeds go directly to the war effort. Olia Fedorova also creates lookalikes, white five-foot-tall paper sculptures in the shape of anti-tank hedgehogs, the steel structures commonly deployed as a line of defense against light and medium military vehicles. She photographs them in a placid snowy field, their minimalist elegance their only strength.

Is this the art these artists would be making had Russia never begun its war against Ukraine? Probably not. Artists make the work they need to, even when at war. It’s the job of the rest of us to see it.

Women at War: 12 Ukrainian Artists continues at the Chicago Cultural Center (78 East Washington Street, Chicago, Illinois) through December 8. The exhibition was curated by Monika Fabijanska.