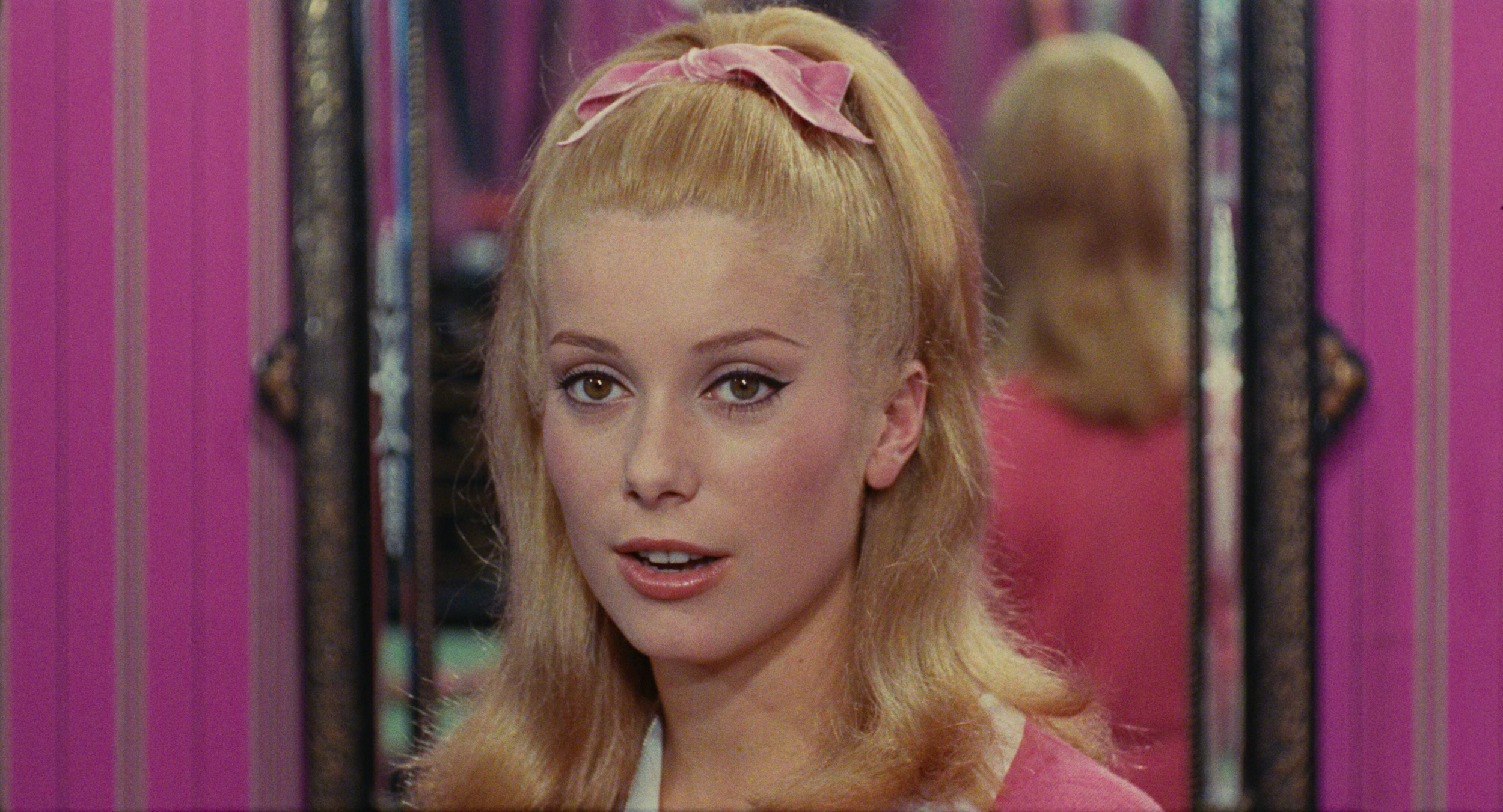

In 1964, Jacques Demy did something unconventionally conventional for the French New Wave — he made a romantic movie musical. Only 33 at the time, the director added a twist: all the dialogue, however banal, would be sung, and by actors with pleasant but audibly amateur vocals. Named for the umbrella shop in which the film’s heroine, Geneviève (Catherine Deneuve), works with her mother (Anne Vernon), The Umbrellas of Cherbourg was a hit around the globe, launching Deneuve into the galaxy of international stardom and Demy into popular renown he would never again experience before his untimely death of AIDS-related illness in 1990.

Now restored to 4k resolution, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is simply one of the most brain-quiveringly beautiful films ever to flood a screen: a hyper-saturated, hyper-feminine deluge of color, texture, and line. Greta Gerwig cited the movie as a key influence for Barbie; Damien Chazelle said the same for La La Land.

Twenty years ago I saw Umbrellas for the first time at an arthouse cinema in Nashville, after it was originally restored under the guidance of Demy’s widow, acclaimed film auteur Agnès Varda. The 2024 restoration, supervised by their son, Mathieu Demy, makes the macaron visuals all the more decadent. Unlike most movie musicals past and present, it is not anchored by a huge ensemble cast, elaborate dance numbers, extravagant sets, or standout vocals. Umbrellas is unapologetically image- and story-driven, with a lush score from Michel Legrand, whose leitmotif, “I Will Wait for You,” will haunt you by the end — an end that is, despite the film’s Candy Crush palette, achingly bittersweet. In Demy’s Technicolor universe, even the petite bourgeoise have reason to sing.

The first shot — of Cherbourg’s humble port — is over two minutes long, the camera craning down at worn cobblestone as rain falls upon it. The umbrellas of sundry passersby, along with the title credits, gesture to the tricolor flag, one of many reminders that this is a French film. Until Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Amélie in 2001, it may be the most conspicuously French film to become a global hit. And like Amelie, the delectable mise-en-scène often distracts from the plot. Unlike Jeunet’s film, though, the setting isn’t Paris, but a shipping town mostly known for a key battle during World War II.

A classic story of love and loss, Umbrellas is just as much about sumptuous color. Less obviously, it is a film about class. The male lead, Guy (Nino Castelnuovo), works as an auto mechanic, the (distinctly French) type to brag to the guys at the garage that he’s ditching a sports match to see Carmen at the theater with Geneviève. Film depictions of blue-collar canoodlers generally adopt a rather dreary color scheme, as though their romantic infatuations literally pale in comparison to those of their blue-blooded peers. But in Umbrellas, Geneviève and Guy stroll the port in complementary pink and blue attire.

“I think only of you, and now you’ll wait for me,” Guy proclaims in one of the film’s many superlative refrains. Geneviève doesn’t wait, of course, but for reasons that seem more justified the older I get. Umbrellas doesn’t patronize its young lovers, no matter how melodramatic their declarations; it honors the depth, however fleeting, of the earth-shattering stakes of their bond.

“Maybe happiness makes me sad,” says Guy’s ailing godmother when she realizes he’s in love. In French, the word for crying, pleurer, is just a few letters away from pleuvoir, which means “to rain.” Umbrellas is a glorious reminder that falling in love, however heavenly, can leave us in tears that feel sent from the sky. It is also a reminder that film, arguably the most pivotal form of visual media in the 20th century, can still transfix in the 21st — especially experienced on a big screen bursting with colors you could eat.

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg screens at the Film Forum (209 West Houston Street, Greenwich Village, Manhattan) December 10–12 and 20.