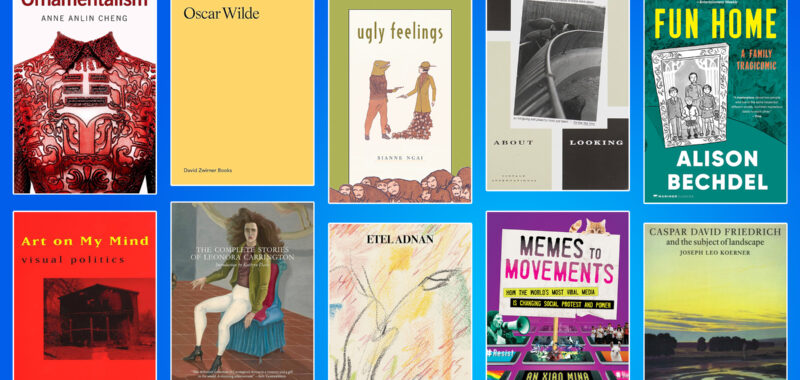

Even though my poor shelf is sagging under the weight of overdue library books and unread novels, I cannot resist a “most-anticipated” list when I see one. But this month, our editors decided to rifle through copies of old art books — or, rather, books publishers deem as such — to unearth titles worth rereading. The new year has already brought devastating wildfires in California, and promises an uphill battle against a new presidential administration and tectonic shifts in the online landscape. As we look ahead to upcoming exhibitions and consider the kind of world we wish to inhabit, reconsidering books that won’t make it onto most industry lists is a way to regain our footing, and perhaps change our minds. Check out a Caspar David Friedrich title before The Met’s show next month, Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir in advance of her new comic’s May release, Hyperallergic critic AX Mina’s timely study of memes, and other old art books we’re rereading in the new year — if only for the sake of your bookshelf. —Lakshmi Rivera Amin, Associate Editor

The Critic as Artist by Oscar Wilde

Centuries before the internet made everyone a critic, Oscar Wilde’s polemical characters Ernest and Gilbert convened around a piano to debate the age-old question: Who needs art criticism, anyway? The two engage in riotous, pathos-filled, and endlessly enjoyable dialogue that I consider a must-read for every aspiring critic and artist. Read it, and then read it again. —Hakim Bishara

Buy on Bookshop | Dodd, Mead and Company, 1891; David Zwirner Books, 2019

Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape by Joseph Koerner

Although I’m long past studying Caspar David Friedrich in graduate school, I still pick up this book at times to enjoy the poetic beauty of both the art and the writing. With a major Friedrich exhibition opening next month at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, it’s an ideal time to invest in this study by Joseph Leo Koerner. Chair of the Department of History of Art and Architecture and professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures at Harvard, Koerner is a consummate art historian; The Subject of Landscape is a deeply informed dive into Friedrich, as well as his influences and cultural context, and, of course, his art. What really sets this apart from other insightful art historical scholarship is Koerner’s own artistry as a writer. Enveloping precise analysis in lovely prose, the book is not only readable but truly engaging — a creative feat in its own right. —Natalie Haddad

Buy on Bookshop | Yale University Press, 1990

About Looking by John Berger

John Berger spent a lifetime in the pursuit of articulating the inscrutable art of looking at art. With a voice so uniquely pure and clear, his writing came closer than any to achieving this lofty goal. Discussing everything from war photography to our relationship with animals, this collection of essays will change how you look at art, and the world at large. —HB

Buy the Book | Rizzoli, 1992

Art on My Mind: Visual Politics by bell hooks

Though the mainstream art world in the United States looked different 30 years ago, late critic and writer bell hooks’s Art on My Mind reminds us of how much has also remained the same. Her book of essays and artist interviews exploring the role of visual art in her own life both diagnoses these deep-seated problems — art writing as pure description rather than critique, curation that pigeonholes Black artists and other artists of color, the problems with categorizations like Outsider Art — and moves beyond them. I found myself dog-earing, underlining, and scribbling question marks in a kind of metatextual conversation with hooks and the artists she writes about, such as Margo Humphreys and Alison Saar. As with her other scholarship, she encourages us to agree or disagree with her. Fittingly, she introduces the text with a moving confession about a painting she made herself: “As Art on My Mind progressed, I felt the need to take my first painting out of the shadows of the basement where it had been hidden, to stand in the light and look at it anew.” —LA

Buy on Bookshop | New Press, 1995

Ugly Feelings by Sianne Ngai

I remember the 2016 United States election well — the horror, the shock, the utter disbelief that we as a nation had elected Donald Trump president. This time around was different for me. We’d been down this path before; my faith in our electorate, opinion of the candidates, and optimism in the American political future had long plummeted to near-bedrock. Sianne Ngai’s Ugly Feelings is the emotional handbook for a year in which we are furious but spent; outraged but limited in our capacity to help; despairing but doomed to continue on with the dreary logistics of living. In contrast to powerful, cathartic emotions — anger, jealousy, sublimity — Ngai deals in those feelings that arise when action isn’t possible: irritation, disgust, and perhaps most pertinent to a new Trump administration, “stuplimity,” her neologism that synthesizes shock and boredom. —Lisa Yin Zhang

Buy on Bookshop | Harvard University Press, 2005

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel

This spring, Alison Bechdel will release an autofictional comic that purports to be about a pygmy goat sanctuary, a TV show about taxidermy, and a viral wood-chopping video. If I trust anyone to rise to such a strange and complex challenge, it’s her. Her 2006 graphic memoir, Fun Home, deftly delineates the contours of art from the stuff of life — layered literary and pop culture allusions are as much visceral as cerebral. She reads, for instance, her father’s passion for painstakingly renovating their decrepit Gothic Revival house by hand as Daedalus-like in its artfulness and obsessiveness. But he is also similar to the labyrinth-maker in his cruelty: “Daedalus, too, was indifferent to the human cost of his projects.”

Bechdel is the foil to her father, particularly in terms of his deep shame about his homosexuality compared to her burgeoning understanding of her own lesbianism and eventual openness about it. “I was Spartan to my father’s Athenian,” she writes at one point. “Butch to his Nelly.” But she, too, is a labyrinth-maker: The same events are repeatedly visited, newly freighted with more information or a different perspective, as if she were stumbling into the same rooms over and over in an attempt to leave. It recalls the heuristics of a hurt mind in its sense of spiraling, but it’s a form of healing and catharsis, too — Bechdel is her father’s daughter, but a different kind of Daedalus. —LZ

Buy on Bookshop | Houghton Mifflin, 2006

The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington, translated from the French by Kathrine Talbot and from the Spanish by Anthony Kerrigan

I’ve often wondered about the before and after of the universes Leonora Carrington conjures in the frozen tableaus of her beguiling, exquisite paintings. What brought these characters together? Where do they go from here, if anywhere at all? A 2017 translation of her deliciously grim 1930s short stories, which rarely end well, seems to delight in confounding us further. That’s all the more reason to plunge headfirst into this thoroughly perplexing voyage, populated by a jungle of cannibalistic faces, a dancing bat named Jemima, and a hyena who dons a human husk at a decadent ball. The New York Review of Books is publishing two of her written works this summer, one long out of print and another translated into English for the first time. In preparation, I plan on revisiting Carrington’s chilling fairytales, treading deeper into the disorienting woods of her shapeshifting imagination, where we may or may not find a path out. —LA

Buy on Bookshop | Dorothy, a publishing project, 2017

Ornamentalism by Anne Anlin Cheng

There are certain themes in our conceptualization of “Asian Americanness” that are so well-trodden they’ve become trite: boba, stinky lunchboxes, the fetishization of Asian women by White men. Something that’s always bothered me about the last point, speaking as a member of the demographic, is how that characterization reinforces our presumed helplessness, our victim-ness, even our object-ness.

Scholar Anne Anlin Cheng’s Ornamentalism (2018) flips that script. “We have spoken so much about how people have been turned into things,” she writes in the introduction, “but we should also attend to how things have been turned into people.” She reads a 19th-century court case in which 22 Chinese women were denied the right to disembark because the immigration commissioner suspected them of being sex workers. From the near beginnings of the American legal system, she points out, race is conflated in the Asian woman not with skin but with clothing and other forms of synthetic adornment.

Cheng’s new memoir, Ordinary Disasters (2024), sees her wrestle with the scholarly ideas of Ornamentalism on a personal level. She explores her love of clothing and traces it back to being raised by a beautiful, fashionable mother. And she muses upon a particularly sickening anecdote in which a 14-year-old Cheng gazes longingly at a pair of shoes in a shop window before turning to see an adult White man staring at her. These two books are perfect counterparts: Ordinary Disasters humanizes the scholarship, while Ornamentalism offers a legal, cultural, and political context that helps soothe the uncanny loneliness that I, at least, have felt when looking upon the image of Asian-American femininity — constructed not just by whiteness but my own people — and failing to find my reflection. This book made me feel a little bit less of a stranger to myself. —LZ

Buy on Bookshop | Oxford University Press, 2018

Memes to Movements: How the World’s Most Viral Media Is Changing Social Protest and Power by AX Mina

It’s hard to overestimate the influence of Hyperallergic critic AX Mina’s book on the intersection of memes and political movements. Written during the last Trump administration, Mina dissects the role of these once seemingly innocuous forms of visual currency in political discourse and how they may be playing a role in protest and dissent. From the memeification of “pussy hats” to the conquest of the internet by cats, Mina forces us not to be wowed by the sometimes seductive images (the book has no illustrations) and consider the underlying ideas that drive our urges to connect through the reproduction of pop culture and familiarity. Mina makes the case that this form of expression, once considered child’s play, is speaking increasingly louder as it becomes a central forum for social change and even conformity. As Donald Trump is set to be inaugurated again, rereading this book is a good reminder that traditional media is increasingly marginalized by the public in favor of contemporary avenues of information dissemination that most people in society still don’t take as seriously as we should. —Hrag Vartanian

Buy on Bookshop | Beacon Press, 2019

Shifting the Silence by Etel Adnan

Published one year before Lebanese-American artist and writer Etel Adnan’s passing in 2021, Shifting the Silence is less stream of consciousness and more a vast sea of poems and vignettes, best consumed in pieces. Adnan writes in the characteristically prophetic voice that infused her visual art. She muses on her own death, considers the many places she has called home, and eulogizes the California landscape ravaged by wildfires, presaging the blazes spreading across Los Angeles County this week. One passage on the limitations of language, its trickery and insufficiency, led me to consider her art as an afterlife of her writing. I wonder what I may have missed in her paintings, what they capture that a prose poem cannot. Luckily, an upcoming show at Manhattan’s White Cube gallery offers a chance to wade through the last 20 years of her decades-long practice.

For all of Adnan’s talk of death, she also offers indelible descriptions of light, the ocean’s rhythm, and silence as a presence rather than an absence — each a creature in its own right. Shifting the Silence primes us to look at her paintings from fresh vantage points, whether the peaks of the California mountains she loved or the rooftop of her home, where she so often sketched the view before her. —LA

Buy on Bookshop | Nightboat Books, 2020